Honoring the Legacy of African-American Cycling Legend Major Taylor

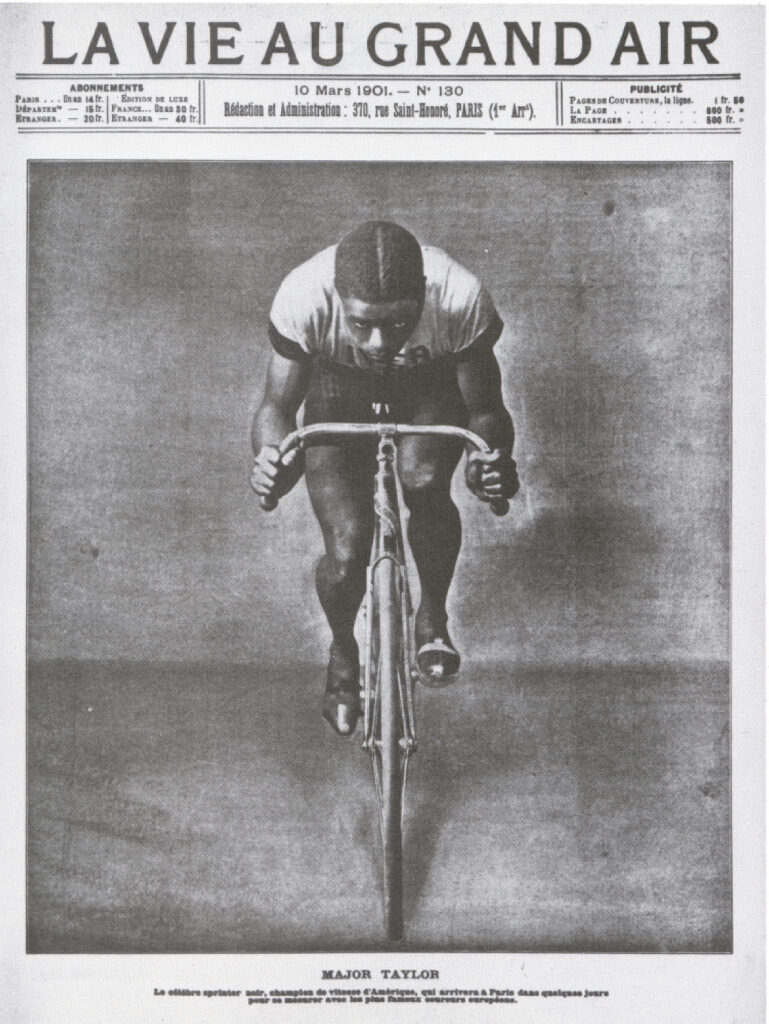

Around the turn of the 20th century, bicycle racing dominated America’s sporting scene, with top cyclists commanding the same media attention that A-list Hollywood celebrities enjoy today. Tens of thousands of fans packed velodromes and road race routes around the world to see the greats compete in events ranging from quarter-mile sprints to six-day endurance rides.

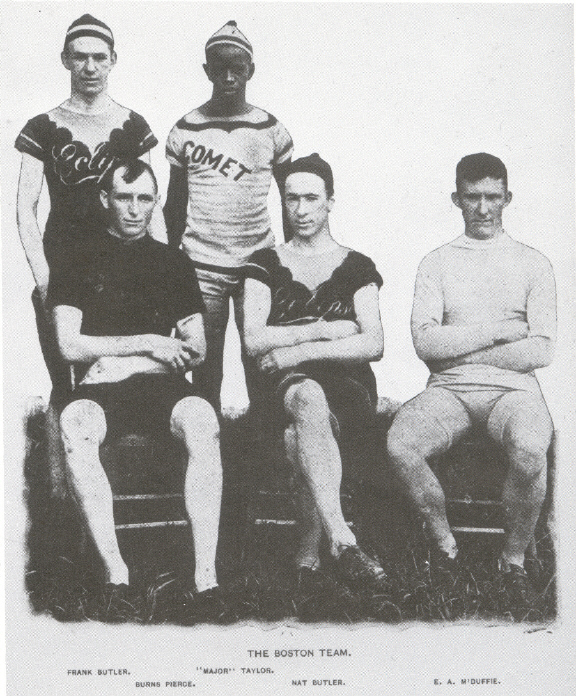

As with other mainstream sports in the U.S., professional bicycle racing was generally understood to be for white competitors only, but in the late 1890s, an African-American dynamo exploded onto the scene, racing at record-breaking speeds that couldn’t be ignored. Today, Marshall “Major” Taylor’s legacy lives on in cycling clubs across the U.S. as well as a popular rail-trail in Chicago, his final resting place.

Life of a Legend*

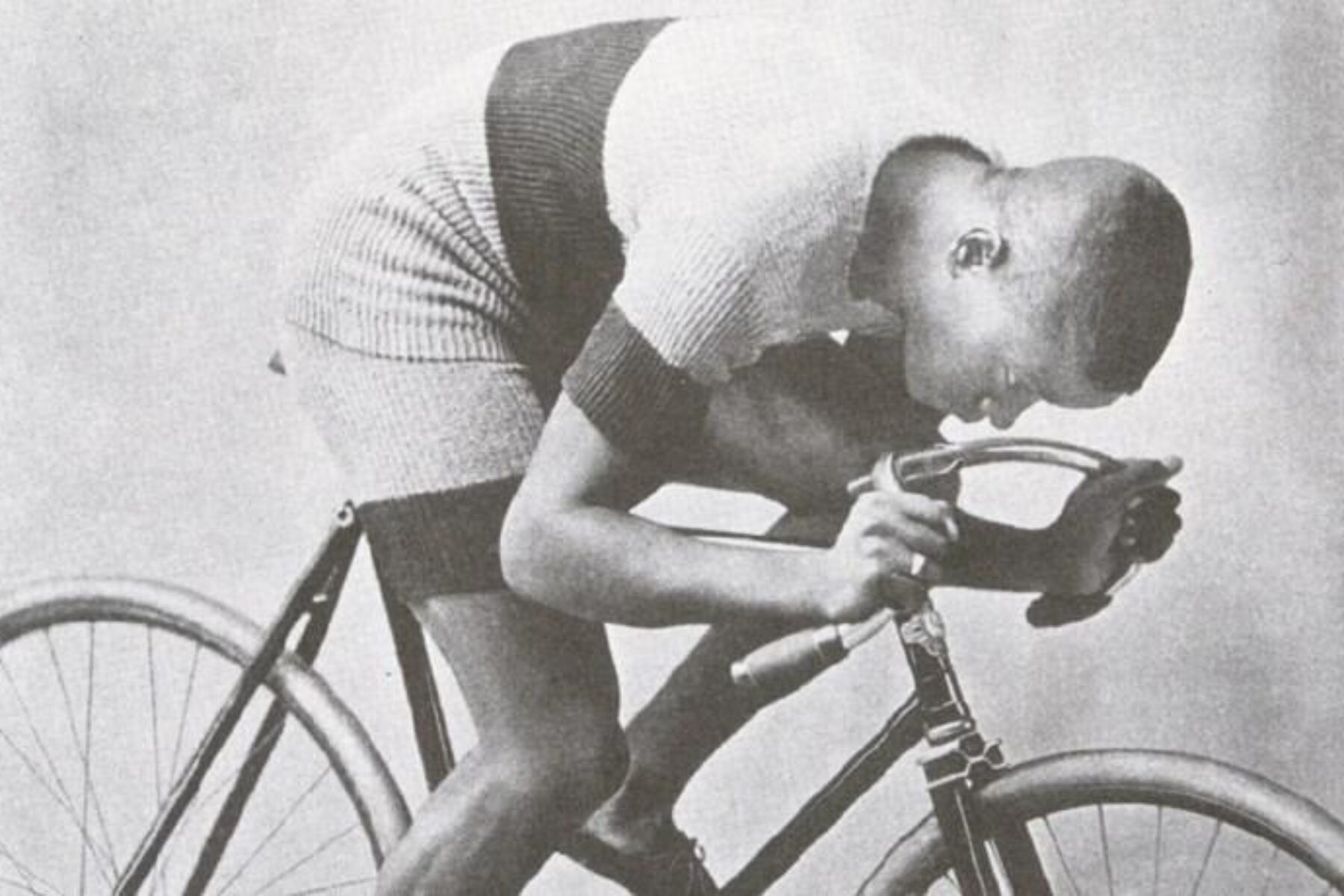

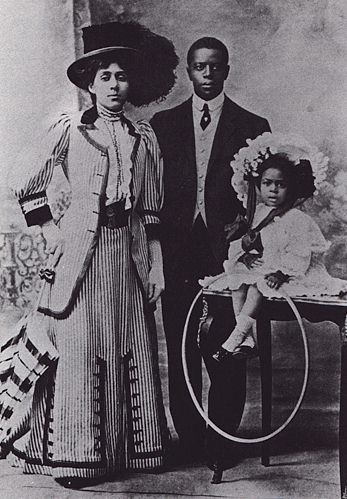

Born Nov. 26, 1878, in rural Indiana, Taylor received his first bike at age 12 as a gift from his father’s employer and quickly taught himself a wide array of tricks. These tricks caught the attention of an Indianapolis bike shop owner, and at age 13, Taylor began his career on two wheels as a stunt rider paid to perform outside the shop. He wore a soldier’s uniform while performing his tricks, leading to the nickname “Major,” a moniker he carried for the rest of his life. The same year, he won his first race, an amateur competition in Indianapolis.

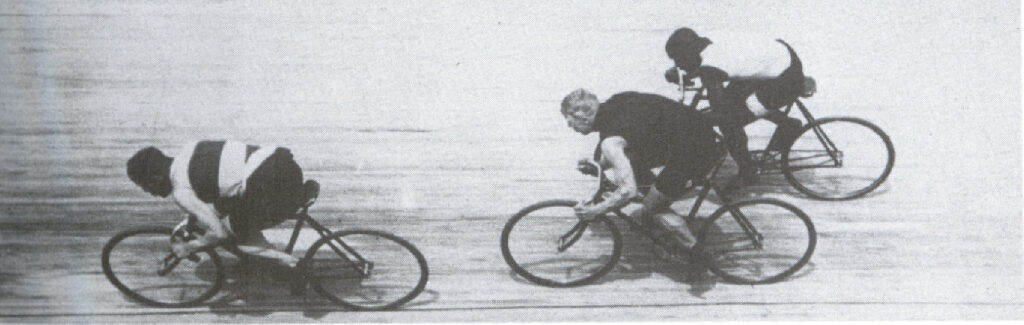

As his teen years progressed, Taylor continued to train and increase his speed, and in 1896, he competed again in Indianapolis, where he broke world track records for paced and unpaced 1-mile rides. Prejudiced race organizers disqualified his times and banned him from the track—treatment he would receive again and again throughout his career.

Many of his competitors felt he should not be allowed to compete in “their” races at all, and his continual wins made him a constant target of racial slurs and physical violence. White riders would crowd him off the track—forcing him to crash and lose his lead—or box him in so he could not sprint toward the front of the pack. During one race in 1897, a competitor knocked him off his bike and choked him to the point of unconsciousness.

When he was allowed to race unencumbered, Taylor obliterated the competition. By 1899, he had racked up seven world records**, and in 1899 and 1900, he won the world sprint championships, making him the first African-American to do so and the second black athlete to hold a world championship in any sport. One of his records, the 1-mile from a standing start, stood for 28 years. Known best for his sprint speeds, Taylor didn’t shy away from distance races as well, at one point racking up more than 1,700 miles during a punishing six-day marathon at New York’s Madison Square Garden. Of the 168 races he competed in before his retirement in 1910, Taylor placed first in 117 and second in 32.

Honoring a Legacy

For years, Taylor’s accomplishments were largely forgotten by the cycling community, but renewed interest around the 100th anniversary of his career peak brought attention to his challenges and triumphs. Taylor lived in Worcester, Massachusetts, during some of his best racing years, and in 1998, residents of that community organized an association to create a permanent memorial, which his adopted hometown erected in 2008.

“Here’s a guy who broke through the color line in sports half a century before baseball player Jackie Robinson, and we think Major Taylor too should be a household name,” says Lynne Tolman, president of the Major Taylor Association, which has since become a nationwide nonprofit that keeps Taylor’s memory alive. “As we learned the details of Major Taylor’s struggle to succeed in the Jim Crow era, we wanted to share the story not only of his athletic achievements but his strength of character. He faced closed doors and open hostility with remarkable dignity.”

The association has grown to include approximately three dozen affiliated cycling clubs across the country, many of whom are named after Taylor, and it has also developed a curriculum guide on Taylor’s life that has been used in schools in more than 30 states. Many Major Taylor cycling clubs predominantly feature African-Americans among their members, and with Taylor’s unyielding grit as their leading example, they seek to use cycling as a way to empower the African-American communities in their areas.

Around the time people in Massachusetts began making plans for a memorial, folks in Chicago began organizing to develop a 7.5-mile trail along an old rail corridor in the city’s southern neighborhoods. Because Taylor spent his final days and is buried in this area, his legacy holds significance for the nearby African-American communities, and trail organizers decided to establish it as the Major Taylor Trail when it officially opened in 2008.

The Friends of the Major Taylor Trail (FOMTT) group, which serves as an advisory council for the trail to the Chicago Park District, collaborates heavily with the Major Taylor Cycling Club of Chicago (MTC3) to encourage bicycling within the community, advocate on behalf of the trail and share information on their local legend.

“Every year, we have an annual club ride to his gravesite on his birthday and do a commemoration in his honor,” says Angela Brooks, former ride captain with MTC3. Peter Taylor, FOMTT secretary, affirms that the two groups actively seek to educate others on the legacy of Major Taylor in their events, which also include a Major Taylor Ride to the River and a Major Taylor Victory Ride. The friends group is also in the process of connecting the Major Taylor Trail to the Cal-Sag Trail by next year, he says, which will greatly improve access to a large network of off-road trails south of Chicago.

To the north, Rails-to-Trails Conservancy and the Major Taylor Bicycling Club of Minnesota are working on legacy projects of another sort. Together, the two groups and their affiliates advocate in support of bicycle and active transportation initiatives that would benefit the Twin Cities, the state of Minnesota and the nation, and they vocally oppose measures that would inhibit safe cycling. Active bills currently before the Minnesota legislature include: a capital investment bonding provision that could provide funding for Safe Routes to Schools, a bike trails bill to establish new bikeways and authorize new official bicycling routes, a motion to regulate cell phone use for drivers, and a bill (opposed by the Minnesota club) that would require users of urban bike lanes to hold a permit.

Bill Dooley, an active member of the Minnesota club and regular advocate for the group’s initiatives at the state capitol, notes that perhaps 70 percent of the club’s members are African-American, and they perform outreach in their community to encourage cycling as part of a healthy lifestyle.

“What we preach when we do these group rides is aimed toward tackling health disparities in the African-American community with transit riding and recreational riding,” he says. “One guy, a transit rider, lost 100 pounds in one year. We tell people, ‘When you go to the store to get bread, jump on your bike.’ People think they need an expensive bike and the clothes and all, but they don’t. More than anything, we want to encourage people just to ride. If you’re going to visit your cousin half a mile away, get on your bike.”

Even with the weight of legislative advocacy and community health on their shoulders, club members still keep their love of cycling at the forefront, and in doing so, they regularly share information on their pioneer namesake.

“We have very colorful bicycle jerseys with the name of the club on them,” says Dooley, “and when we’re participating in the context of a larger ride, somebody will usually ask, ‘Who was Major Taylor?’ and we’ll get to talk about him. We try to share his history whenever we get a chance, like when we’re leading community bicycle rides during warmer months.”

More than just remembering a noteworthy athlete, these groups are truly honoring Major Taylor’s memory by working positively toward inclusive communities that support active cycling and an equal playing field for all. Undoubtedly, he would be pleased to see the progress made since his years of struggle and perseverance.

*Special thank you to the Major Taylor Association, the Major Taylor Bicycling Club of Minnesota, the Major Taylor Cycling Club of Chicago and Friends of the Major Taylor Trail for providing the source material for this blog.

**Note: Some sources indicate he set seven new speed records in 1898 and did so again in 1899. These ranged in distance from 0.25 mile to 2 miles.

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.