Five Amtrak Stations Along the Great American Rail-Trail

A few years ago, Justin Marquis and Zyzzy Balubah biked from Amsterdam to Berlin using trains to connect different starting and stopping points.

“It was such a convenient, enjoyable experience that we thought we should do this in the United States,” said Marquis, a seminary student. So they did. In the summer of 2025, the couple began a string of train-to-trail adventures beginning from their hometown of Chicago, which included taking Amtrak’s Cardinal Limited route to Cincinnati to pick up the Ohio to Erie Trail; taking the Lake Shore Limited train to New York’s Empire State Trail; and hopping on the Missouri River Runner to reach the famed Katy Trail State Park.

Balubah appreciates the affordability of train travel, but for her, the best part about using Amtrak between trails is that “the journey becomes part of the vacation. You get to relax and watch the scenery go by.” One other lesser-known perk? In their experience, “bikers board first.”

As the Great American Rail-Trail® continues to take shape across the country, Amtrak offers cyclists an inexpensive and fun way to keep the good times rolling between trailheads. Here are five train stations along the trail’s route between Washington, D.C., and Washington State.

FAQ

Check out Amtrak’s “Bring Your Bike Onboard” page for an extensive set of information and an FAQ on how to navigate their stations and trains with a bicycle.

Stations and lines along Amtrak vary in terms of their policies related to whether bikes are permitted and how they should be transported and stored. You can view a national trip-planning map for Amtrak on their website. RTC list extensive trail and route information for the 3,700-mile Great American Rail-Trail on their website, and you can also access information, including maps and other detailed resources, for more than 42,500 miles of multiuse trails at TrailLink.com.

Union Station (Washington, D.C.)

Located less than a mile from the easternmost end of the Great American Rail-Trail, Union Station is one of the oldest and most iconic train terminals in the country. The most recognizable feature of the beaux-arts-style rail station, opened in 1907, is its 26,000-square-foot main hall, where 22-karat gold leaf adorns the 96-foot vaulted, coffered ceilings.

In its heyday, Union Station employed a staff of 5,000 and offered an impressive array of amenities, including a bowling alley, Turkish bath, nursery and mortuary. While you can no longer opt for a hot soak, you’ll still find plenty to do in the station between trains. Stash your bike and bags in Amtrak’s temporary bag storage ($20 an item) and browse the shops for a new book or artisan chocolates. Grab a quick coffee or linger over a long lunch. The U.S. Capitol, the National Mall and the many museums of the Smithsonian Institution are an easy walk from the station, as is the Library of Congress and the National Portrait Gallery.

Nearby bike shops The Daily Rider and Silver Cycles both offer replacement accessories, repairs and tune-ups before it’s time to hit the trail.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2026 issue of Rails to Trails magazine and has been reposted here in an edited format. Subscribe to read more articles about remarkable trails while also supporting our work.

Harpers Ferry Train Station (Harpers Ferry, West Virginia)

Step off Amtrak’s Floridian service in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, and you’ll feel like you stepped back in time. The historical wood-frame depot, opened in 1894, was designed by E. Francis Baldwin, the architect who built more than 100 train stations for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, recognizable by their distinctive style and red-and-brown color schemes. The original station had two waiting rooms—one for men and one for women—with roaring fireplaces to warm passengers while waiting for the train.

Perched at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers—as well as at a crucial juncture between the North and the South during the Civil War—Harpers Ferry was the sight of abolitionist John Brown’s famous raid. Today, the town looks a lot like it did during Brown’s time, with narrow cobblestone streets lined by 19th-century homes and businesses. Much of the town lies within Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, where visitors can wander between a number of interpretive exhibits and historical buildings—including the armory where Brown and his men barricaded themselves during their ill-fated uprising. (Learn more in Rails to Trails’ Winter 2025 issue.)

Before hopping on the Great American, which follows the C&O Canal Towpath through town (and is accessible via a pedestrian bridge adjacent to the station), stop by Harpers Ferry General Store to pick up supplies for the journey, everything from seat covers to freeze-dried camp meals. Staff there can also arrange for a local shuttle to nearby hotels and grocery stores.

Joliet Gateway Center and Union Station (Joliet, Illinois)

Visitors to the Chicago suburb of Joliet, Illinois, will find not one but two train stations to explore. Gateway Center, opened in 1912, is a modern depot featuring a comfortable waiting area and small café. It also houses the Joliet Railroad Museum, which offers exhibits on the many railroad companies that have operated in the city—as well as the centuries-old controls that coordinated the movement of trains through the Midwestern hub.

Just across the tracks sits Joliet’s historical Union Station, built in the early 20th century to alleviate the congestion caused by the four trunk lines that served the city (the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific; Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe; Chicago & Alton; and Michigan Central), all of which maintained their own depots. The neoclassical revival building was designed by noted railroad station architect Jarvis Hunt. Today, the former passenger waiting area—a soaring space clad in Tennessee marble and bronze finishes—has been transformed into a ballroom popular for weddings and community events.

Joliet, a stop along Amtrak’s Lincoln Service and the Texas Eagle line, is located in a 3.5-mile gap of the Great American, between the western terminus of the Old Plank Road Trail and the eastern terminus of the Illinois & Michigan Canal State Trail. While in town, consider enjoying a Joliet Slammers baseball game at Duly Health and Care Field or a performance at Rialto Square Theatre, both within walking distance of the train stations.

Omaha Amtrak Station (Omaha, Nebraska)

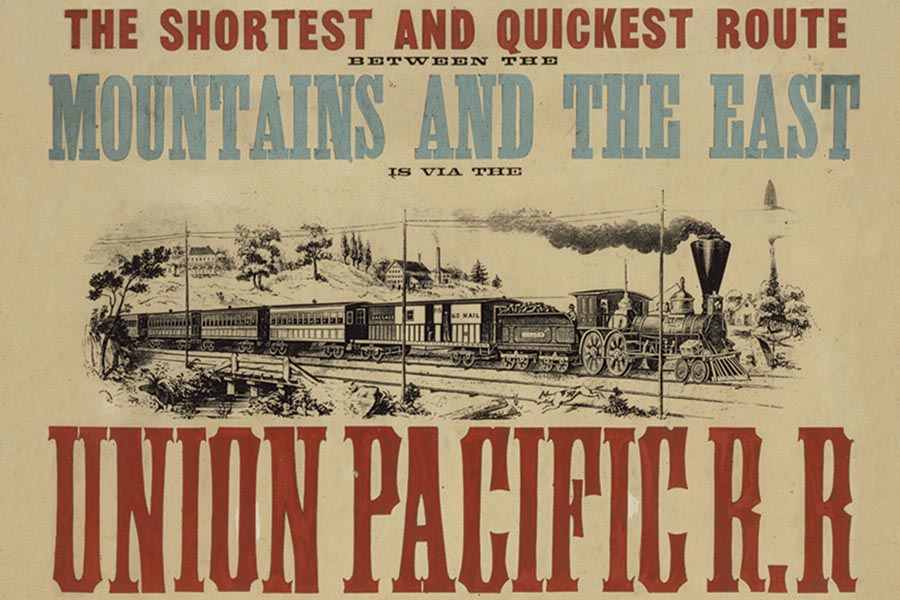

Omaha, a stop on what is perhaps Amtrak’s most storied route—the California Zephyr (a two-day trip from Chicago to San Francisco)—is also a standout stop on the Great American. Here, you can cross the 3,000-foot-long Bob Kerrey Pedestrian Bridge just north of town. Visitors can learn about the railroad’s legacy on both sides of the bridge: at the Union Pacific Railroad Museum in Council Bluffs, Iowa, and at Omaha’s Durham Museum, housed in the city’s former train station, an art deco masterpiece. (Learn more about Council Bluffs’ Mile 0 legacy on the nation’s first transcontinental railroad.)

Today’s Amtrak station, opened in 1984, is decidedly less ornate than its predecessor, but it is located steps away from the city’s Little Italy neighborhood, an enclave steeped in the cultural and culinary heritage of the Sicilian immigrants who arrived in the early 1900s and helped build the Union Pacific. Once you’ve gotten your fill of pizza, pasta and cannoli, head to the RiverFront, a 72-acre downtown park where you can learn about another famous cross-country journey at the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail visitor center.

King Street Station (Seattle, Washington)

Since it opened in 1906, Seattle’s King Street Station has been an indelible part of the city’s economy and its skyline. A brick and granite three-story building with a striking 12-story clock tower, the station is served by three long-haul Amtrak routes: the Cascades, the Coast Starlight and the Empire Builder (the latter named after James J. Hill, financer of the station and builder of the only transcontinental railroad to be privately funded).

Before heading out to explore the city, check out the 7,500-square-foot gallery at ARTS at King Street Station, a studio space dedicated to increasing opportunities for People of Color to generate and showcase their work. Then head to Seattle’s Chinatown Historic District, adjacent to the station. The first Chinese immigrants arrived in the region in the late 19th century and found ample work building the region’s railroads. Today, the neighborhood’s Wing Luke Museum tells the story of the Asian American experience in the Northwest.

Just a few blocks west of the station, you can pick up the Seattle Waterfront Pathway, which is part of the Great American. The trail takes you past the bustling Seattle Ferry Terminal, the Seattle Aquarium, the city’s massive Ferris wheel and other attractions, as well as offers views of Elliott Bay.

How to Ride the Rails to Ride Your Bike

Using trains to begin, end or connect your rail-trail adventure means you can kick back and enjoy the scenery as you travel between trailheads. But fair warning: Pulling it off does require planning ahead and doing your research, as space can fill up quickly.

“Because our rail equipment varies in different parts of the country, the ability for our trains to carry bikes without having to disassemble them also varies,” explained Marc Magliari, a senior public relations manager for Amtrak. “For example, the new trains that we’re running in the Midwest have bike racks built into them, so you can roll on or roll off, but the trains that go overnight, for the most part, do not.” On trains without built-in racks, bikes are stowed in the baggage car either fully assembled or broken down into a box.

The easiest way to find out if your bike will be treated as carry-on luggage (heads up: some racks require removing the front wheel) or checked baggage is to visit Amtrak’s web page about its bike policies. You’ll need to head there anyway, to make a reservation that includes your bike. Prices range from $5 to $20 for the one-way add-on; bike boxes are $25 and can be reused.

When it’s time to travel, make sure you arrive at the station early. Check in with a customer service agent to get a claim check and learn where on the train your bike will be stored. You will also need extra time to disassemble any parts of the bike necessary for the type of service your train offers.

During transfers or at the end of your journey, you will either remove your bike from the on-board bike rack or meet an attendant at the baggage car to retrieve it. At smaller stations where baggage-check service is not available, speak directly with the nearest Amtrak crew member when your train arrives. Be aware that Amtrak currently does not accommodate non-standard bicycles like tandems, trikes, recumbents or bike trailers. E-bikes up to 50 pounds are allowed on board.

If you have questions about your specific train’s bike service, go to the ticket counter, advises Zyzzy Balubah, a frequent train-and-bike traveler [see full story]. “In our experience, they are very eager to help you,” she said. “They will help you find solutions to get your bike aboard.”

And if you’re looking to really travel light, Magliari suggests procuring a bike at your destination. Expanded bike share and bike rental options across the country, he said, “have lessened the need for people to feel like they need to bring their bike.”

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.