Before Lewis and Clark, there was Moncacht-Apé

Around the late 1600s, a Native American explorer is said to have crossed the continent a century before the famed Corps of Discovery. Parts of his route can be followed today along multiuse trails.

“I had lost my wife, and the children that I had by her were dead before her, when I undertook my trip to the country where the sun rises,” began Moncacht-Apé, a Yazoo elder, in a mid-1720s recounting of his noteworthy life.

Moncacht-Apé was visiting Antoine-Simon Le Page at his blufftop home in the French colony of La Louisiane near present-day Natchez, Mississippi, where he spent several days narrating his travels to the fascinated Frenchman. A farmer and historian, Le Page was friendly with neighboring tribes, and when he inquired about their origins, some members would point him to the far northwest.

Learning of Le Page’s curiosity, Moncacht-Apé had come 80 miles from the Yazoo River. Decades before, he said he’d embarked upon his long journey to answer the same question about the tribe’s origin. While the French called Moncacht-Apé “the Interpreter” for his gift with languages, the meaning of his Yazoo name was particularly apt for the explorer: the killer of difficulties or fatigue.

Moncacht-Apé’s account was published by Le Page during the 1750s in articles and a book, later translated into English as “The History of Louisiana.” Since that time, scholars have debated the validity of his journey and, as a result, it tends to be lost in the shadows of the famous Lewis and Clark expedition. Yet many observers find the details of the story not only plausible but probable, which would make Moncacht-Apé the first recorded explorer to reach both U.S. coasts. Lewis and Clark are even said to have carried a copy of the book about Moncacht-Apé’s travels on their 1804–1806 expedition.

Travels in the East

After departing his village, somewhere near present-day Vicksburg, Mississippi, Moncacht-Apé began his journey east by visiting his neighbors, the Chickasaw. Then the explorer turned northeast, desiring to see the Great Water that he’d heard about. He typically walked 10–15 miles per day, carrying clothing and a bedroll, a pot and bowl, and a bow and arrows. He followed the winding Ohio River eastward through the country of the Shawnee and the Iroquois.

He spent a snowy winter in a northern village of the Abenaki, perhaps somewhere southeast of Lake Champlain (which sits between modern-day New York and Vermont). There he befriended another explorer who would become his guide and travel partner. Moncacht-Apé was not used to such a long and cold season, and he struggled with homemade snowshoes to hunt bison that once ranged into the Northeast. Come spring, he and his friend continued east. They traveled carefully and rested often, as their feet became sore from negotiating rocky terrain. After several days, they reached a windy cliff overlooking the Great Water (the Atlantic Ocean) that he’d come to see.

“I was so content, that I could not speak,” he recalled.

Moncacht-Apé stayed in the Northeast for over a year, spending another long winter with his friend’s family in the Abenaki village. The next spring, the twosome traveled west across what became Upstate New York to see a rumored waterfall. They reached the Niagara River north of present-day Buffalo. For half a day, they followed the current downstream as a thunderous sound grew.

“The sight made my hair stand on end and my flesh creep,” said Moncacht-Apé. But after gathering courage, he descended to the base and crept inside the airspace behind the plunging Niagara Falls.

The next day, the friends went south to the upper Ohio River, near present-day Pittsburgh. Using a hatchet, they made a dugout canoe from a soft-wood tree. Though he’d seen much and met many tribespeople, he’d learned little of his ancestors. Then he bid goodbye to his friend, and Moncacht-Apé took to the water and returned to the Yazoo Nation.

Following Moncacht-Apé’s Route in the East

In time, the Native American routes followed by Moncacht-Apé became major corridors for white settlers and U.S. transportation, including shipping waterways and railroads that later became recreational trails.

In the east, the likely route from the Abenaki village to the Niagara River would have paralleled the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor. The 360-mile Erie Canalway Trail, which crosses Upstate New York between Albany and Buffalo, is a relatively flat and mostly offroad path that’s perfect for day excursions and multiday tours.

Moncacht-Apé’s coastal camp was likely somewhere near Maine’s Acadia National Park, which today has 45 miles of multiuse gravel carriage roads that are popular for walking, cycling and horseback riding.

Midwestern Route

The spring following his return home, Moncacht-Apé departed his Yazoo village and went north along the eastern shore of the Mississippi River. He intended to journey west from nation to nation until he reached the lands of his ancestors—a trek that would take him some five years. In the country of the Illinois, he built a raft and crossed above the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers near present-day St. Louis. Then he went westward overland along the northern bank of the muddy Missouri. Upon finding the tribe of the same name, he wintered with them and learned their language.

When the snows melted, Moncacht-Apé traveled to the Kanza tribe (from which the state of Kansas derives its name), who described a difficult route to the Otter nation and a river flowing west. Crossing the prairies, there were herds of bison for miles, so he hunted and ate well. For a month, he followed the Missouri River, while the surrounding hills grew to mountains that he feared to cross.

In the grasslands, he met a party of hunters who spoke an unfamiliar language. Communicating with signs, he was invited to join a husband and wife who were returning to their people, the Otters. After two weeks, first following the river and later venturing over the Continental Divide, they reached a clearwater stream they called the Beautiful River.

For weeks, Moncacht-Apé traveled with a canoeing party of Otters heading west on what became the Columbia River in present-day Idaho or Washington. They stopped regularly to hunt and fish, portaging their canoes when necessary. The explorer waited out the peak heat of summer, and later he wintered with a nation somewhere along the Beautiful River. Always, he spent time with tribal elders who enjoyed teaching their languages and ways. Eventually, he continued alone, frequently encountering smaller tribes as he approached the Great Water of the West.

Following Moncacht-Apé’s Route in the Midwest

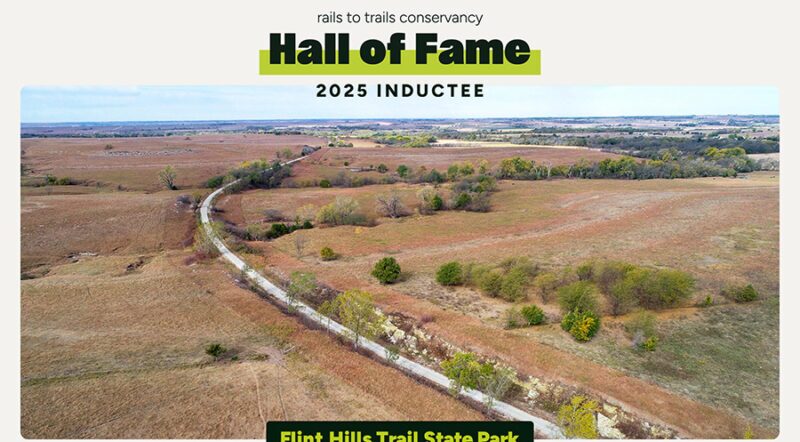

Moncacht-Apé’s route along the Missouri River overlaps with the present-day Katy Trail State Park, one of the longest rail-trails in the country. The gravel path stretches across most of Missouri through bottomland forests and rolling farmland from St. Charles, on the outskirts of St. Louis, to Clinton, southeast of Kansas City. The eastern 161 miles of the trail follow the river’s northern bank, which Moncacht-Apé describes in detail.

The Journey West

Moncacht-Apé reached the Pacific Ocean during a state of conflict between coastal tribes, and he joined a fight against invaders from the sea who came to harvest trees. With this episode, the Yazoo traveler offered one of two reasons that some observers later dismissed his story. Moncacht-Apé described the invaders as mysterious bearded white men, but claimed they did not resemble the French, English, or Spanish that he knew.

The second inconsistency came from Moncacht-Apé’s vague descriptions of his generally northwesterly route. Some scholars have suggested that the account led later explorers, Lewis and Clark, to expect an easy crossing of the Continental Divide. When they instead experienced a month-long struggle in the Rocky Mountains, it led many to dismiss Moncacht-Apé’s story as inaccurate or fabricated. However, Le Page and others believed that Moncacht-Apé convincingly described geographic features that would later be confirmed by European and American explorers.

Moncacht-Apé never reached the homeland of his ancestors, but he did come close. Before returning east, he traveled north along the Pacific Ocean. In one village, the elders explained that the coast continued for a great distance north before extending west and ending in an ocean strait. At one time, the land had continued. Their people came from somewhere beyond. With this information, Moncacht-Apé began his long journey home.

Following Moncacht-Apé’s Route in the Pacific Northwest

In the Pacific Northwest, Moncacht-Apé’s route traced the scenic Columbia River Gorge. Near Umatilla, Oregon, the Lewis and Clark Commemorative Trail offers up-close views of the river along a 7-mile gravel route best suited for mountain bikes. Additionally, the Historic Columbia River Highway State Trail provides roughly 19 miles of paved pathway east of Portland with overlooks of the gorge, waterfalls and historical bridges and tunnels.

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.