Oregon’s Crown Zellerbach Trail

Trail of the Month: Nov. 2022

“The Crown Z is the start, or the end, of a three-trail system that will take you from the Columbia River to the coast.”

—Casey Garrett, a Columbia County commissioner

Winding 25 miles through the northwest corner of Oregon, the Crown Zellerbach Trail (affectionately nicknamed the Crown Z Trail) serves as a rolling journey into history, introducing visitors to the home of the region’s First Peoples, the legacy of the area’s railroad and timber industries and intriguing geological events.

Although once neglected, continued investment by Columbia County and its close-knit communities have turned the former railroad corridor into an outdoor asset for locals and a draw for residents of Portland just over 20 miles away.

“It’s a 30-year project in the making, but there’s been a steady vision to keep it moving along,” said Casey Garrett, a Columbia County commissioner.

Garrett grew up in this area, and he and his friends rode their motorbikes on the logging roads, which are now part of the trail. “I never would have guessed it would turn into this recreational [feature],” he said.

After years of work by dedicated volunteers and public servants, the trail opened in 2014. Its eastern end travels through the town of Scappoose, then winds among deciduous trees before heading into conifer forests as the elevation increases. It reaches its highest point at a little over 1,200 feet at Nehalem Divide, before ending, at around 500 feet, in Vernonia. Mountain bikes work especially well for the trail, which is largely packed gravel, and—with a trailhead every 3–4 miles, trail users can hop on for a short hike or ride or make an entire day of it.

“The lower section is closer to the [Columbia] river, and there are a lot of kids riding their bikes, particularly because it’s near town,” said Matt D’Agrosa, an environmental scientist and co-creator of WildColumbia.org, as well as a local who loves the trail.

A Path Through History

Millions of years ago, when there was abundant volcanic activity in the region, magma flows traveled along the Columbia Basin all the way to the Pacific Ocean. The exposed basalt flow is evident along the trail, as well as the markings of younger (albeit 100,000 to 14,000 years ago) glacial flooding events. Although the trail is some 50 miles inland from the coast, visitors can even find seashells in some of the sedimentary deposits along the route.

“There’s a lot of cool geology along the trail,” explained D’Agrosa. “Just being able to look for the geological formations adds something [to the experience].”

From these ancient cataclysmic events grew lush forests and green landscapes where First Peoples thrived for eons, and the trail’s interpretive signs share many of their stories.

“This was the most densely populated area in the U.S. [for Indigenous Peoples],” said Cindy Ede, part of the Friends of the Crown Z Trail. “It literally was a metropolis around Scappoose.” The name of the town comes from Skáppus, the village of a Chinookan tribe, and this entire region was home to the Chinook and Clatskanie people.

Throughout her life in this region, Ede has championed the history of the First Peoples and has worked to protect artifacts and important sites. Near Scappoose, the Meier Site preserves the remains of a 55-by-90-foot Chinookan plankhouse that housed 200 people, and archaeological evidence is found throughout the trail and the region.

In addition to the fish available in the nearby Columbia River, Ede also noted that Bonnie Falls, which is a short jaunt off the trail, is a prime example of where salmon were frequently caught during their spawning period as they worked their way up the falls. “That was a fish encampment right near the trail,” she said.

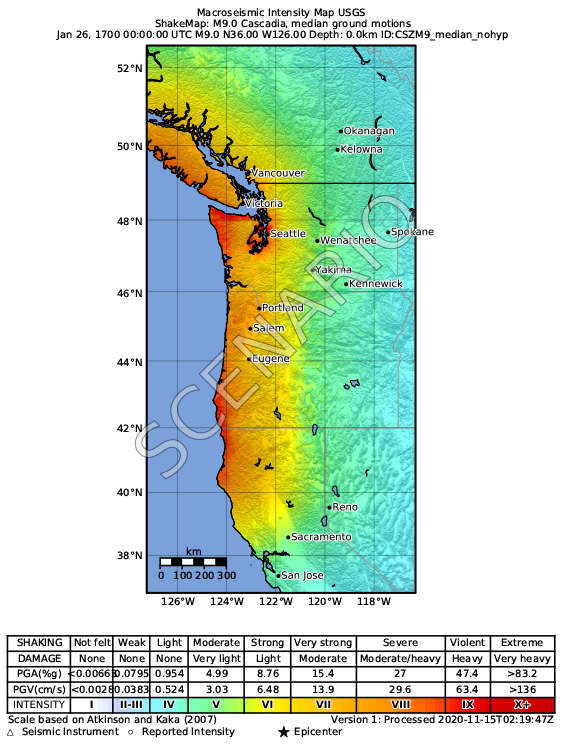

subduction zone by the United States Geological Survey | Courtesy U.S. Geological Survey

As a result of abundant natural resources, these advanced, permanent villages thrived for eons, and according to documented evidence, part of the Crown Zellerbach Trail leading to Sauvie Island most likely follows the footsteps of these Indigenous People.

In January 1700, a major earthquake (estimated to be a magnitude of 8.7–9.2) hit the Pacific Northwest and unleashed a tsunami that devastated the coastal people, particularly the Chinook. A few years later, Spanish explorations of the region began. By 1828, settlers had moved into the resource-rich area, and in the mid-1800s, the federal government began a removal of the area’s remaining Indigenous People.

In 1906, Simcoe Chapman and his son incorporated the Portland and Southwestern Railroad, expanding the line as needed for logging operations here. Even though the railroad changed hands several times over many decades, the line was in use until 1943. The following year, the Crown Zellerbach Corporation purchased it and removed the tracks to create a road for logging trucks.

Today, 34 kiosks along the trail explain the area’s

geology and wildlife, as well as provide historical information created by the Columbia County Museum Association with QR codes (where there is cell service) for additional content.

While there was initial pushback with concerns that a popular trail would negatively impact the area, Garrett said locals now realize its benefits, especially since many of the perceived problems never materialized. “They take a certain pride in the area,” he noted, particularly when it comes to their logging heritage. “Even the names of the trailheads have history behind them,” he added.

Pathway Partnerships

In addition to the kiosks, many of the trailheads also include restrooms, picnic tables and bike repair stations. All of this work, as well as other improvements for the trail, are a concerted effort by a number of public and private partners.

“Community support has been instrumental in our work,” said Dale Latham, member of the Crown Zellerbach Trail Citizen Advisory Committee. “In addition to the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department, Travel Oregon and the Columbia Economic Team have been key funders.”

Garrett noted that they have also consistently worked with timber companies, including Weyerhaeuser and Holce Logging Company (which granted an easement into Vernonia), as well as the Bureau of Land Management, for rights-of-way throughout the county.

“The Crown Z is the start, or the end, of a three-trail system that will take you from the Columbia River to the coast,” enthused Garrett.

At its westernmost trailhead, wayfinding signage guides users into Vernonia over the 2 miles of shared road and directs them to the nearby 21-mile Banks-Vernonia State Trail. This ultimately connects to the developing 86-mile Salmonberry Trail, which begins northwest of Portland and will stretch all the way to the Pacific Ocean, ending at Tillamook.

While the backbone of the Crown Zellerbach Trail is well established, Garrett said, “There is a lot more to do.”

Related: Trail of the Month: Banks-Vernonia State Trail (Jan. 2016)

Related: Trail Tourism Adventures Await Along Salmonberry Corridor in Oregon

Related Links

Trail Facts

Name: Crown Zellerbach Trail

Used railroad corridor: Portland Southwestern Railroad

Trail website: Friends of Crown Z Trail

Length: 25.8 miles

County: Columbia

Start point/end point: Chapman Landing at 51738 Dike Road (Scappoose) to the Holce Trailhead at 1780 E. Knott St. (Vernonia)

Surface type: Primarily packed gravel; just over 2 miles of the eastern end of the trail near Scappoose is paved.

Grade: The general grade of the eastern end of the trail is less than 5% for its first 11 miles heading west from Scappoose. From there, the maximum grade is 12% near Nehalem Divide and 20% near the Holce Trailhead in Vernonia on the western end of the trail.

Uses: Walking, mountain biking, horseback riding and cross-country skiing; wheelchair accessible for its first 2 miles in the Scappoose area

Difficulty: The Crown Zellerbach Trail ranges from easy—with more than 2 paved miles near Scappoose—to moderate. The eastern end of the trail is relatively level for 11 miles heading west of Scappoose, then climbs to Nehalem Divide before dropping down and gaining elevation once again past Wilark near Vernonia on the western end of the trail.

Getting there: The Portland International Airport (7000 NE Airport Way) is approximately 55 miles from Vernonia and 25 miles from Scappoose. Travelers can also arrive via Amtrak at Union Station (800 NW Sixth Ave. Portland).

Access and parking: Parking is available at the following trailheads, listed from east to west along the trail:

- Chapman Landing Trailhead: 370 feet southeast of the intersection of E. Columbia Avenue and Dike Road in Scappoose

- Scappoose Trailhead: NE Crown Zellerbach Road, 0.1 mile east of W. Lane Road

- Pisgah Trailhead: Scappoose-Vernonia Highway, 0.1 mile northwest of Wikstrom Road

- Bonnie Falls Trailhead: 30715 Scappoose-Vernonia Hwy

- Ruley Trailhead: Scappoose-Vernonia Highway, 0.4 mile west of Hale Road

- Floeter Trailhead: Columbia Forest Road Travel and Hawkins Road, 75 feet north of Scappoose-Vernonia Highway

- Holce Trailhead: 1780 E. Knott St., Vernonia

To navigate the area with an interactive GIS map, and to see more photos, user reviews and ratings, plus loads of other trip-planning information, visit TrailLink.com, RTC’s free trail-finder website.

Rentals: Bike rentals are available in Portland, approximately 20 miles southeast of the trail’s Scappoose end, from bike shops such as Everybody’s Bike Rentals and Tours (305 NE Wygant St., Portland; phone: 503.358.0152) and Cycle Portland (117 NW 2nd Ave., Portland; phone: 844.739.2453).

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.