Heritage Corridor: How the Farmington Canal Heritage Trail Is Sparking Connections and Community Prosperity in Connecticut

In 2015, Ray Charpentier, diagnosed with multiple sclerosis a decade earlier, fell off his bike at a red light in Manchester, Connecticut. Struggling to get up, he feared it marked the end of his cycling days. “My balance was so bad,” Charpentier, now 61, said. “I was like, ‘I can’t do this anymore.’”

He shared this experience at an appointment with his exercise therapist at Mount Sinai Rehabilitation Hospital in Hartford and got some advice: Go see Ken Messier at Ti-Trikes, then in nearby Simsbury. Started as a joint effort with NASA to help injured veterans at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center with their medical rehabilitation, the titanium framed, pedal-assisted recumbent Ti-Trikes had proven beneficial to riders with a number of health issues, like multiple sclerosis (MS), Parkinson’s disease and strokes.

Charpentier went, and Messier loaned him a Ti-Trike to try across the street on the nearby Farmington Canal Heritage Trail (FCHT).

“It’s crazy—it changed my life,” said Charpentier, who’s since started a nonprofit to help other New Englanders with disabilities get back to riding. “That’s when I really started to recover from MS.”

The protected stretches of the FCHT helped Charpentier regain confidence. Since that first test ride, he’s logged over 10,000 miles on Ti-Trikes.

While Messier said the Ti-Trike was designed for people to use on all kinds of roads—he first tested it with a 3,900-mile Connecticut to California cross-country journey that included only about 100 miles of protected trail—he said he wants customers to feel safe and protected on that first one to get used to the experience. “We’ve always believed that for people to test ride, they’ve got to be in a safer environment than on the road,” Messier said.

Since the 1990s, the Farmington Canal Heritage Trail has offered safe passage to people bicycling, running, walking, commuting and exercising across a growing number of Connecticut and Massachusetts miles. From the south, it rolls through Yale University’s storied campus before linking New Haven neighborhoods to Hamden, Cheshire and Southington. Farther north, a longstanding gap in Plainville is soon to be filled, before continuing up through Farmington, Avon and Simsbury en route to the Massachusetts border, where its Bay State miles are about two-thirds complete. In both states, it’s become a magnet for trail connections. (See sidebar.)

Developed piecemeal on a former canalway turned railway through citizen-led efforts, the trail has gained widespread buy-in from neighboring communities and state-level partners. It also serves as a key link along the ambitious East Coast Greenway, a 3,000-mile, 15-state project. In Simsbury, a trailhead sign lets hikers, bikers, runners, cross-country skiers and other trail users know the distance to each of the East Coast Greenway’s eventual endpoints: 706 miles to Calais, Maine; 2,194 to Key West, Florida. (The skiers might want to aim for Calais.)

This article was originally published in the Winter 2025 issue of Rails to Trails magazine and has been reposted here in an edited format. Subscribe to read more articles about remarkable trails while also supporting our work.

To the Finish Line

While the East Coast Greenway is about 35% complete, longtime FCHT advocates can see a finish line of sorts in Connecticut. About five or six years from now, they say, the final Connecticut gaps should all be filled, providing trail users with a protected 56.5-mile path from the New Haven shore to the Massachusetts state line. The Massachusetts portion of the path, once finished, will run about 25 miles, from Southwick to Northampton. It’s about 65% complete.

With plans and funding in place to close the final 9.1 miles of Connecticut gaps, Bruce Donald, Southern New England manager for the East Coast Greenway Alliance, said the focus will turn to trail maintenance and marketing as it nears its completion.

Trail design has evolved since those first pieces opened in the 1990s, and Donald said there’s an ongoing conversation with state officials about widening older segments, clearing out invasive species and the like. Donald said the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) awarded a Recreational Trails Grant to update a regional guide to the East Coast Greenway that spotlights history, businesses, and natural and cultural features along the trails that take you from New Haven to Providence, Rhode Island. Asked to look ahead to what will happen once the final gaps are closed, Donald said, “Probably the biggest thing is, don’t be shocked at the enormous growth in tourism.”

As the final gaps in New Haven and Plainville are filled, Donald said talks are underway to streamline trail signage. As you get closer to Massachusetts, for instance, you see signage calling it the New Haven and Northampton Canal Greenway.

“There are like three [different] mile zeroes right now,” Donald said. “But we know where the trail is going to go, both in New Haven and in Plainville. So as early as next year— might be two years—we’re going to go for a Rec Trails [Recreational Trails Program] Grant … and re-sign the entire trail so we’ll have the various local and regional logos, mileage, economic wayfinding signage—and really do it correctly. And again, that comes with having a mature trail.”

While many of the decisions are to come, Donald said trail advocates know where the official mile zero will be located: New Haven’s Boathouse at Canal Dock, a fitting starting point for a trail built along what started as a 19th-century shipping line.

“It’s very empowering that that is going to be mile zero for the trail,” said Lisa Fernandez, president of the Farmington Canal Rail-to-Trail Association, adding that it is helping to build connections between downtown New Haven and the waterfront, “a cultural and historic touchstone for Connecticut for more than two centuries,” and the birthplace of the trail’s namesake canal line that connected New Haven to the hinterlands.

New England Connections

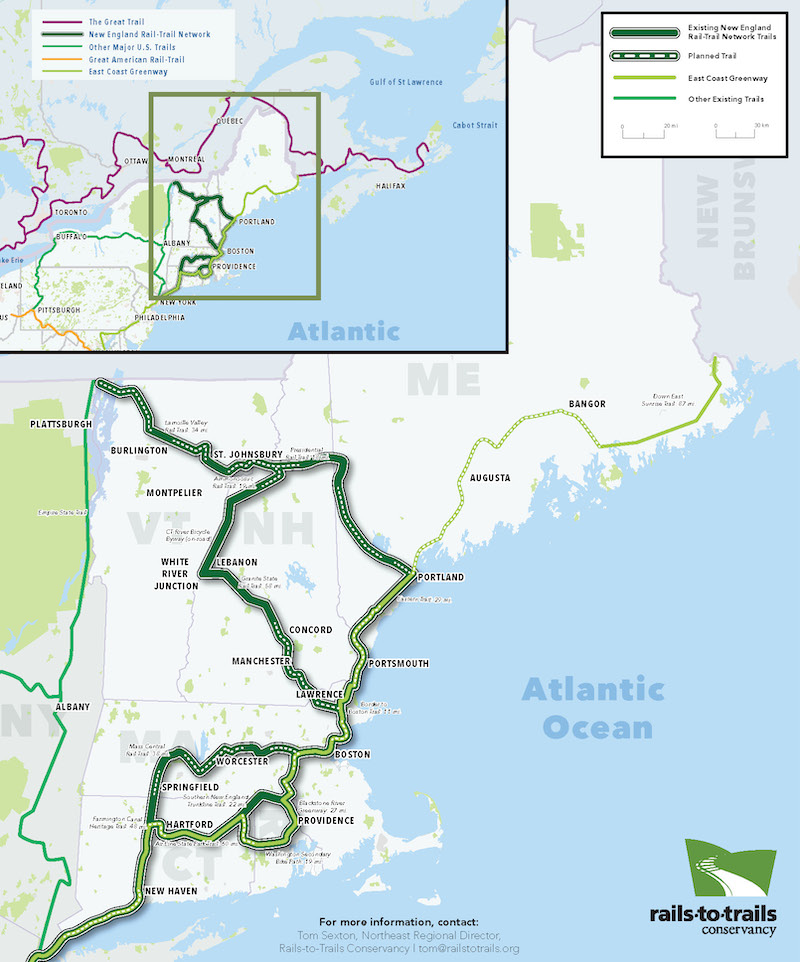

With most of its Connecticut miles complete and efforts underway to build some major connections, the Farmington Canal Heritage Trail (FCHT) is a key piece of the burgeoning 1,200-mile New England Rail-Trail Network. From Simsbury, you can either depart the trail and head east toward Hartford and Providence, or keep moving north on the FCHT toward Massachusetts, where the right-of-way becomes the New Haven and Northampton Canal Greenway.

Up north, gaps remain along the 25-mile path between Southwick and Northampton. There, the trail connects to another major New England Rail-Trail Network host, the east–west Mass Central Rail Trail, which will eventually cross through 20 communities to Boston. (About 60 of the 104 miles are open.) Down south, funding is in place to connect the FCHT to the Shoreline Greenway Trail, a proposed 25-mile corridor connecting several coastal Connecticut communities.

In the middle, efforts are also underway to link the FCHT with the Airline State Park Trail, a project that would connect Connecticut’s two longest trails. These efforts are part of an even more ambitious effort to build out a 111-mile Central Connecticut Loop.

And if you need a loop now, you’re in luck. In Farmington, trail users can hook to the west to take a longer, scenic path to Simsbury via the Farmington River Trail. Combined with the FCHT path, the trails form a roughly 28-mile loop with only a few on-road miles.

History of Its Own

Just a short walk from the Cheshire trailhead parking lot—nearly filled to capacity on a brisk early-November Saturday—you can find a restored section of the Farmington Canal. It’s part of Lock 12 Historical Park, which also includes a small museum featuring a blacksmith and carpenter displays. In the 1820s, New Haven investors built a canal inspired by the Erie Canal. The construction of the New Haven section was led by William Lanson, a free Black engineer and prominent area businessman. No image of Lanson has survived, but in 2020, a bronze statue of Lanson by sculptor Dana King was erected adjacent to the trail (at 8 Canal Street) to honor his life and contributions to New Haven’s development.

Unfortunately, soon after the canal opened in 1828, it was outdated, and canal traffic dried up by the late 1840s. “It was really only a canal for a very short amount of time and was never successful economically,” Fernandez said. “And then very quickly, it was the beginning of the railroad era. So they just kind of developed it too late for it to prove to be an economic boon.”

The canal was soon replaced by the New Haven and Northampton Railroad, which became vital for transporting goods along the north–south corridor.

Like many railroads, it changed hands and ultimately began to disband in the 1980s. Piece by piece, the abandoned line was converted to rail-trail in a state where political power remains rather community oriented—so much so, said Fernandez, that many people in Connecticut still speak of the 169 towns (the number of municipalities with distinct geographic boundaries in the state).

In the south, Fernandez said the trail’s earliest development was tied to a citizen-led effort to oppose a new mall being planned in Hamden. Activists in the New Haven County communities of Cheshire and Hamden petitioned for the Canal Line to be repurposed as a community recreation trail. The first 6 miles there opened in 1996.

Now open for almost three decades, the trail next to the Lock 12 park has established a history of its own among residents and visitors alike. Sydney Forlano and Michael Broyles were finishing a ride at the same time I was. The couple met in New York, and Forlano, who now lives in Bethany, was taking Broyles, an Oklahoma native, on his first ride there. For Forlano, it’s a special place.

“For the first years of my life, I lived right down one of these side streets up here,” Forlano said. “And it was just me and my mom, really, and she would always put me in like a baby carrier and bike up and down this trail.”

Up north, members of the Farmington Valley Trails Council, which formed in 1992, initially worked with town governments in Avon, Farmington, Simsbury, Suffield, Granby and East Granby to match federal dollars provided for trail development through the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991, which established Transportation Enhancements (now Transportation Alternatives) and the Recreational Trails Program. Together, they are the largest source of federal funding for trails and walking and biking infrastructure today.

Like many other early rail-trail development efforts, Donald said the first pieces that now comprise the FCHT were piecemeal and orphaned, but they were soon embraced by residents of the communities that installed them. And, Donald said, “adjoining communities said, ‘Look at this.’”

“I think we have a very holistic view of what the trail is and what it can be. It’s not just for recreation. It’s for commuting. It’s for transportation. It’s an economic development tool.”

—Aaron Goode, New Haven Friends of the Farmington Canal Greenway

Making the Case

As Donald and I talked on a memorial bench near the Iron Horse Boulevard trailhead parking lot, I tried to keep count of the walkers, runners and others who passed by. Over the course of an hour, there had to be over 20 or 30 passersby during the first cold-cold weekend of late autumn.

Turns out you don’t need to ballpark trail use in Connecticut though, thanks to a statewide effort to install infrared tracking sensors along all the state’s major trails. Donald, a stockbroker before he became a trail advocate, helped lead the push to put this system, called the Connecticut Trail Census, in place. “I have always wanted to have quantifiable, academically rigorous data, and we now have that in Connecticut,” Donald said. “We’ve got about four years of it now, and in some cases more than that with the Connecticut Trail Census. And that has been an eye opener, particularly for higher-up elected officials and for the [Department of Transportation].”

The trail data isn’t just available to government officials. The University of Connecticut houses a public, online dashboard as part of the UConn CT Trails Program. With funding from DEEP’s Recreational Trails Program, the university leads three statewide projects: the Trail Census, Connecticut Trail Finder and People Active on Trails for Health and Sustainability (PATHS).

The census presents up-to-date trail counts at a growing number of locations across the state. The Simsbury sensor, for example, is located just north of the Ironhorse Boulevard trailhead where Donald and I met. The Connecticut Trail Census in mid-November reported that an average of 127 trail users daily had passed by the laser counter installed in Simsbury over the dates tracked in 2024. The numbers are slightly down from the spikes seen across the Farmington Canal Heritage Trail, and all trails, during the height of the pandemic. But they remain well above the Simsbury sensor’s numbers from 2018, the first-year trail data was collected there.

Across the trail, Donald said, the census shows about a 30% spike in usage during the pandemic, which has tapered off by only about 12% since. “We retained a lot of those new users,” he said.

Thanks to the time stamp the censors collect when a person passes by, as well as regular manual surveys, advocates also know how people are using the Farmington Canal Heritage Trail.

“It’s about 50-50, according to the data we’ve gotten from the Connecticut Trail Census, in terms of recreational trips versus other types of trips: commuting, work, school, shopping, doctors, appointments, etc.,” said Aaron Goode with the New Haven Friends of the Farmington Canal Greenway. “We can see people using it at commuting times; they’re not just using it on Saturdays and Sundays during the summer. They’re using it year-round, and they’re using it during the 7–9 a.m. and 4–6 p.m. periods. And we can go to the city [with this data] and say, ‘People need to use this for all these essential trips, and you really need to plow this trail in the wintertime.’ So it has a kind of utility in terms of making the case. … And we knew all of those things before, but it’s different when you have hard data.”

He continued, “I think we have a very holistic view of what the trail is and what it can be. It’s not just for people in spandex. It’s not just for weekend warriors. It’s not just for recreation. It’s for commuting. It’s for transportation. It’s an economic development tool.”

A Sense of Ownership

About a mile from the stately Yale University campus is the Newhallville neighborhood, a historically under-served community of about 7,000 people that transitioned from an Italian population to a majority Black population during the Great Migration. “It’s a post-industrial neighborhood,” said Doreen Abubakar, founder and executive director of CPEN-Community Placemaking Engagement Network. “And we all know what that brings.”

Nowhere was that more evident to Abubakar than in a blighted public space along the Farmington trail known as the Mudhole, once recognized as a crime hotbed. Now, it’s the Learning Corridor, and Abubakar said its proximity to the trail has inspired many of the opportunities offered to Newhallville residents there. CPEN’s space now offers urban farming, pollinator gardens, a bike repair station, an ebike share rack, exercise equipment and more.

It started, Abubakar said, with a water fountain.

Fewer than half of Newhallville and neighboring Dixwell residents asked in a 2018 survey reported that they were in very good or excellent health, well below the Connecticut average. They also reported higher rates of obesity, diabetes and heart disease compared to Connecticut averages. The trail, Abubakar said, should help these residents address their wellness needs the same as it does for runners, walkers and cyclists who are passing through. At the beginning of the effort to transform the Mudhole, she sought out funding for a state-of-the-art water fountain. The Farmington Canal Rail-to-Trail Association, she said, “was our No. 1 sponsor.”

The same day she asked, she received a commitment for $5,200 to install a water fountain that Abubakar spoke about proudly during our conversation. “Our water fountain has a water bottle filler and a dog tray and a place that we can hook up a hose to water our gardens,” said Abubakar. Partnership efforts like this have multiplied since that initial agreement with the trail association. The Bradley Street Bicycle Co-op earned a grant to lead bike repair classes in the corridor and set up a repair station, and their staff also lead youth rides, one of many efforts to build the Learning Corridor into, as the website says, “a symbol of communal prosperity within the Farmington Canal Greenway.”

Fernandez said Abubakar has excelled at creating a sense of ownership among residents of not only the Learning Corridor, but also the trail.

“And I think what I’ve been able to give back is that we are utilizing the trail,” Abubakar said. I met Abubakar and Fernandez at Fussy Coffee, right along the trail, the morning after clocks rolled back an hour. That afternoon, she had plans to give out free bike lights to Newhallville kids. Down the road, Abubakar said she is exploring how to connect more Newhallville residents with disabilities and seniors to the trail.

Up the road, Ray Charpentier has made that his mission. After getting comfortable on the Farmington trail with his Ti-Trike, Charpentier started signing up for every Bike MS ride in the region. Then he started encouraging others to join him. Charpentier founded the nonprofit Support Info-Go Initiative, an effort “to connect people with medical conditions to the resources they need to live happy, healthy lives.” In many cases, one of those resources is Charpentier’s growing fleet of trikes.

Pre-COVID, Charpentier led Saturday morning rides, often on the Farmington trail, and during one of them five years ago, a man who’d suffered a debilitating stroke said, “Ray, look at me.” Charpentier didn’t notice anything at first, until he looked at the handlebars of the trike. “This guy had no use of his right arm,” he said. “He had both hands on the handlebars. It was insane.”

His next big ride is a summer fundraiser he’s organizing in Windsor, where he lives. In Simsbury, where we met, Charpentier used the interview as an opportunity to put some more miles in on the Farmington Canal Heritage Trail.

“You can’t say enough about having a trail like this,” he said before riding down the leaf-covered trail. “I’m just in awe of it.”

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.