A Nebraska Legacy: Examining the Cowboy Trail’s Impact Across Three Decades

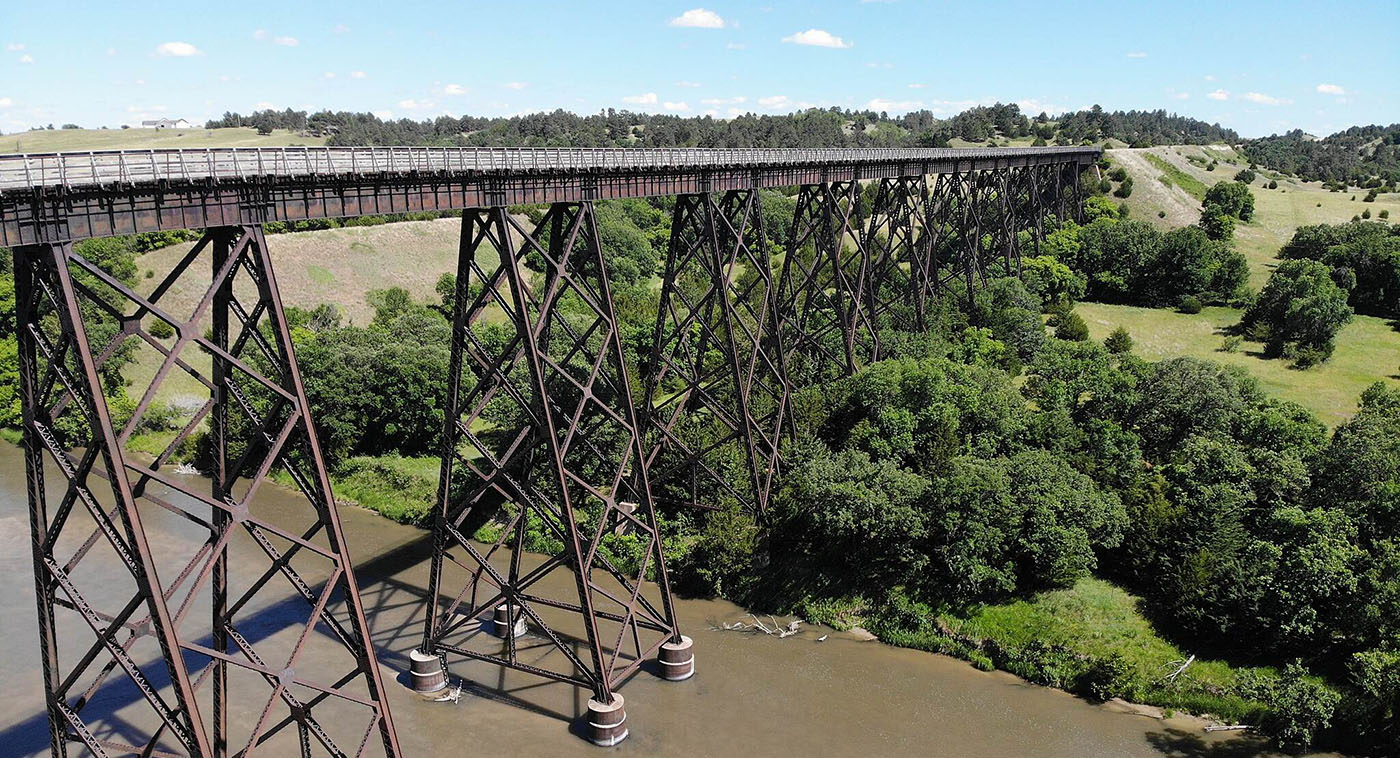

On the way back to their respective homes following a family visit to Valentine, Nebraska, Michael and Pam Swanson and their daughter, Ashley Schafer, parked at a trailhead off U.S. Highway 20 to take in the panoramic view of the Sandhills from the longest of the 221 bridges that dot the Cowboy Recreation and Nature Trail.

About the Cowboy Trail

When complete, the Cowboy Recreation and Nature Trail will be a boon for tourism across Nebraska, connecting 30 rural communities and all four of the state’s distinct ecoregions. Learn more about this trail, which turns 30 in 2025, on TrailLink™ or outdoornebraska.gov.

Counties: Antelope, Brown, Cherry, Holt, Madison, Rock, Sheridan

Length: 317 miles (currently 203)

Endpoints: Rushville to Gordon; Valentine to Norfolk

Uses: Walking, Biking (including Class 1, 2 and 3 e-bikes), Horseback Riding, Mountain Biking

The Niobrara River glided through the valley below them, shallow enough in late July for weekend float trippers to drag their feet across the bottom and for the bridge’s visitors to view the riverbed from their perches 148 feet above it. Stopping by the trail’s signature bridge was something of a tradition.

“When the children were growing up, we probably came up here 16 years in a row, and this was always part of our stop,” said Michael Swanson, of Malmo, Nebraska. Now Schafer, who lives in Norfolk, has kids of her own, and her family often hops on the Cowboy Trail at its eastern starting point, about 200 miles from Valentine.

“We take our bikes out on the Cowboy Trail, and sometimes we start at Ta-Ha-Zouka Park, and then other times we go out to Broken Bridge,” she said. It’s a reason for her and her family to get out in nature, a feature the Cowboy Trail offers in abundance.

Across its full, potential 317-mile path, the trail covers over 5,000 acres of wildlife habitat and touches each of the state’s four distinct ecoregions: the tallgrass, mixed-grass and shortgrass prairies, as well as the signature Sandhills of north-central Nebraska.

“It really gives you a great opportunity to see, up close, each of these ecoregions and how they differ from each other and the different species that inhabit these different areas of our state,” said Alex Duryea, recreational trails manager for the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, which maintains the trail. “And frankly, I think doing that via the Cowboy Trail by bike or by horse or by walking is the kind of speed you need to be at in order to really see and experience those differences. You just don’t see that kind of stuff when you’re traveling at 65 miles an hour.”

Improving Infrastructure Across the “Bike Shop Desert”

Part of the allure of the Cowboy Trail is finding community and beauty where others aren’t looking. But good luck finding a replacement derailleur.

“You’ve heard of a food desert,” said Julie Harris, executive director of Bike Walk Nebraska. “We have a bike shop desert.”

Norfolk Bike, near the trail’s eastern terminus, is the only one around.

In 2022, Bike Walk Nebraska established the Cowboy Trail Coalition to seek funding and development opportunities for more miles, to promote economic development and safer passage via trails, and to help water the desert. Harris said they help communities find grants for bike fix-it stations, or provide them directly, when they partner on the kinds of projects that trail towns prioritize. Chadron, Valentine, Neligh and Norfolk are among the communities that have bought in, she said. On her wish list: Developing a partnership between local auto parts stores and a bike part distributor, so if a cyclist broke down in, say, Bassett, she could get the missing piece quickly shipped there.

But first, more fix-it stations. When we spoke, Bike Walk Nebraska was gearing up for a fundraiser with the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission in Valentine to install bike fix-it stations and make trailhead improvements there as part of the Cowboy Trail’s 30th anniversary celebrations. “We recognize the diamond in the rough that [this trail is] for bicycle tourism and for the communities along the trail,” Harris said.

Celebrating 30 Years

This year, as one of numerous efforts tied to the 30th anniversary celebration of the Cowboy Trail, Nebraska Game and Parks published a Cowboy Trail Field Guide designed to help trail users not only know what fauna and flora to look for across its respective regions—burrowing owls and swift foxes in the shortgrass; pronghorn and sand milkweed in the Sandhills—but also to help build closer connections with the trail.

Duryea celebrated the guide’s launch by inviting people to take a full-moon evening hike on June 11 and stargaze above a bend in the Elkhorn River along the Broken Bridge a little west of Norfolk. “We had about 100 people, and it was really nice,” Duryea said.

Once completed, the Cowboy Trail will span 30 rural Nebraska communities, from Ta-Ha-Zouka Park in Norfolk to just outside of Chadron. Along with bringing users closer to northern Nebraska’s natural beauty, it connects the region’s present and past. In Long Pine, you can breathe in forest terpenes from atop the trail’s second-tallest bridge and also bunk for the night in the former railroad barracks just down the trail. What once was a weighing station in Newport now serves as a 24/7 pool hall and snack bar to passersby, all on the honor system. Farther east, you’ll find the only brick depot still standing in O’Neill, now refurbished and serving as the Holt County Economic Development office. And agribusiness is omnipresent.

From an open window on the third story of the Neligh Mill, you can listen to the nearby Elkhorn waters that powered the production of 98,000 pounds of flour a day during the Progressive Era. In nearby Laurel Hill Cemetery, you can join countless residents and visitors who have paid respects to White Buffalo Girl, an infant who died there of pneumonia soon after the U.S. government forced the Ponca Tribe from their nearby land to present-day Oklahoma (read “The Legacy of White Buffalo Girl, and the Resiliency of a People”). Her parents were allowed only a brief ceremony to grieve; her father, Black Elk, asked Neligh’s residents to look after his daughter’s grave as though it belonged to a child of their own. It is sure to be adorned with flowers and other offerings when you visit.

Seeing the connective value of the former Chicago and North Western Railroad,Rails to Trails Conservancy purchased it in 1994 for $6.2 million and handed the deed over to the State of Nebraska. Once completed, it will become the longest path along the cross-country Great American Rail-Trail®. Currently, the Cowboy Trail runs generally alongside U.S. highways 275 and 20. It’s uninterrupted from Norfolk to Valentine for 202 miles, save for a detour in Oakdale around a bridge approach lost to the catastrophic floods of 2019 (read “From Recovery to Resilience”) and a section between Neligh and Clearwater reclaimed by the Elkhorn River.

The spring 2019 floods caused roughly $7.7 million in damages to eastern portions of the trail, while also illustrating its importance to the rural communities it links. With many roads out, the limestone trail served as a passageway for emergency personnel. Some ranchers, seeking the highest ground available, led their cattle to the Cowboy Trail.

Repairing the flood-damaged rail line segments in the east proved to be a major setback to trail expansion way out west. The only segment west of Valentine that’s functional is a 17-mile stretch from Gordon to Rushville that was surfaced only after local advocates not only politicked, but pulled the weeds and remaining rail ties from the ground themselves. But steam is picking back up west of Rushville, and another 25 miles of trail could be surfaced by the end of 2026.

Remote Challenges—and Allure

Duryea once went town by town across the map of what would be a finished version of the Cowboy Trail and counted up the residents. About 26,150 people call Norfolk, the largest city on the trail, home. Add up recent Census data of the rest of the communities running west out to Chadron and the population base still falls about 35,000 people shy of filling Lincoln’s 85,458-seat Memorial Stadium, home to the Nebraska Cornhuskers.

For touring cyclists and hikers, the remoteness of the Cowboy Trail presents obstacles both challenging and alluring. In the Sandhills, you’re sure to pass through verdant grasslands and likely to endure slower split times. Windblown sand can saturate trail segments across the central corridor, requiring the Nebraska Game and Parks maintenance team to respond to frequent reports filed by trail users. You’ve got to look out for tire-shredding goat’s head thorns, although several people I spoke with said the Nebraska Game and Parks crew has done yeoman’s work when it comes to thinning them out along the trail. The Cowboy Trail team consists of a superintendent, two seasonal workers and, during a ride with me and a photographer, Duryea pausing now and then to hack at the occasional musk thistle.

It’s often double-digit mileage from one town to the next; self-sufficiency is part of the deal unless you sign up for one of a growing number of group events happening on the trail, like the Cowboy 200. The 84-hour time-limited foot race from Norfolk to Valentine was set to take place in late September. Traci Jeffrey, executive director of the Norfolk Area Visitors Bureau, said the organizers reached out to her a few years back asking for help to offset the costs of starting it. It fit with the tourism bureau’s MO of supporting events tied to the city’s waterways and trails.

“We said absolutely—anything to promote the Cowboy Trail,” Jeffrey said. “They get people from all over the United States. I know even just this year, just looking at some of the participants for that, they are from Iowa, West Virginia, Virginia, Illinois. And they’re all coming for that particular event, and they’ll spend the night. And of course, when they spend the night, it’s that domino effect in your community of going out to eat and maybe picking up something that they’re going to need for their [race] along the way.”

There is assistance, however, for individuals and groups who wish to experience the Cowboy Trail in other ways. Tony Stuthman, a Norfolk-based outfitter, runs a shuttle service for Cowboy Trail visitors. He and Duryea both patrol a Cowboy Trail online forum, where Duryea often chimes in with advice ranging from what gear to bring (extra tubes, 1.8-inch-plus tires) to where to refuel (Ma’s Cafe in Wood Lake, the L-Bow Room in Johnstown), and Stuthman coordinates rides from afar.

“That’s one of the reasons I did start [this business]—so that people had the opportunity to get out there,” he said.

In rural Valentine, you can even grab a bike from ROAM Share, possibly the most rural bike-share program in the world.

The money visitors spend at rural cafes, grocery stores and gas stations can help keep those establishments in business for the residents who rely on them, Duryea said. That kind of economic impact, he said, is vital along the Cowboy Trail. Duryea estimated that around 80% of the Cowboy Trail’s users are local, and he’s seeing buy-in growing. During a late July ride, he stopped where Norfolk’s paved city trail met the Cowboy’s limestone alongside the Elkhorn River. At the base of a flagpole, there was a metal box. Inside were a few trinkets picked through by participants in the Cowboy Cache program he started this year to celebrate the trail’s 30th anniversary. Duryea ballparked that 100 people would participate. About 600 people already had by late July, and Duryea was dealing with the good problem of trying to find freebies to replenish his popular program.

While he didn’t have 2025 data cleaned up, automatic counters in the towns between Valentine and Norfolk totaled 87,000 trips along the trail over the first half of 2024. But its remoteness and its breadth make for many DIY projects for volunteers, including weeding, changing a flat or building out miles-long western segments.

“I think we’ve done a lot of good.”

Three times a year, Cowboy Trail West volunteer Ross Elwood, 78, gets on a Farmall tractor four years older than he is and putters up and down the 17-mile segment of the Cowboy Trail between Gordon and his home of Rushville, mowing along a path that he and a grassroots group first cleared of towering weeds and heavy debris about a decade ago.

“It was such a mess,” said Elwood, who’s owned a parts store in Rushville for nearly six decades. “That first year, we picked up 60 truckloads of debris between Rushville and Gordon.”

Like many who’ve helped form and sustain the nonprofit Cowboy Trail West, Elwood joined in after hearing the story of Kris Ferguson’s 2011 car-bike crash on Nebraska Highway 27, which intersects with the trail in Gordon. When Ferguson heard the first voicemail Elwood left her, she put off returning his call because she thought he’d have an opinion along the lines of the rancher who told her, “I’m sorry you got hit, but we don’t need a trail.”

Instead, Ferguson found one of many allies who would move heaven and earth with her to build the momentum needed to develop and sustain the trail. Now, Elwood is preparing to retire his mower. Funding is in place for Nebraska Game and Parks to take over maintenance and expand the Cowboy Trail’s reach. A seasonal worker will soon manage a 41-mile stretch from Gordon west to just outside Chadron, including 25 miles still in development.

Asked what he’d do once Nebraska Game and Parks took over, Elwood laughed: “I might get on my bike and go for a ride.”

That level of support didn’t happen overnight. “Let me preface this by saying that Nebraska Game and Parks has actually been amazing,” Ferguson said. “But the first call I made [to them], the comment I got was, ‘We are never building trails in Nebraska again.’”

Undeterred, she canvassed the area, gathering petition signatures. Other local residents joined her effort. “They also wanted a safe space,” Ferguson said, “and that turned into our nonprofit, which is Cowboy Trail West.”

At first, it was hard for Ferguson to talk about the crash that broke her leg and arm, bruised her lung, and left her concussed. But her story resonated. “My story is the most known piece of the puzzle, but I can’t take more credit than any of the other board or community members. It’s been a labor of love.”

Emphasis on labor: The group attended meetings, raised funds, cleared land and maintained the trail themselves. It officially opened in 2019.

“I think we’ve done a lot of good,” Elwood said. “We’ve decked five bridges and put handrails on them from Rushville to Gordon. And our volunteers are just awesome.”

Nearly everyone who helped form Cowboy Trail West in 2012 remains on the board. Ferguson, now in Arizona, still participates. Last spring, she returned for the “Meet Ya in Clinton” ride, co-hosted with Nebraska Game and Parks to celebrate the trail’s 30th anniversary. Riders met in Clinton, population 38, where dinner—served by women at the town’s church—warmed up cyclists after a cold, windy ride.

The trail, Elwood said, has brought the community together. Whether it’s making sure the Warrior Expedition riders feel at home during the veterans annual ride on the Great American Rail-Trail® or building birdhouses to put them on mile marker posts, someone steps up.

Building Miles, Momentum and a Mountain Bike Track

“We’d seen what Cowboy Trail West had done with the Cowboy Trail and said, ‘Hey, we’ve got to get our end going.’”

—George Ledbetter, Treasurer, Northwest Nebraska Trails Association

In Chadron, a group is working to match the energy—and mile markers—of the Cowboy Trail West nonprofit.

George Ledbetter, treasurer of the Northwest Nebraska Trails Association (NNTA), was inspired by South Dakota’s George S. Mickelson Trail, which he lived by in the Black Hills, to create a rail-trail in Chadron after meeting others who shared the idea. “We’d seen what Cowboy Trail West had done with the Cowboy Trail and said, ‘Hey, we’ve got to get our end going,’” he said.

With Nebraska Game and Parks having recently decked the bridges between Rushville and mile marker 400, the trail’s western terminus, and surfacing tentatively set for 2026, Ledbetter said he’s excited to ride the first new section of Cowboy Trail in years. “That was what first spurred us on with our organization, was to get that part done,” he said. The NNTA is now focused on a 5-mile gap between the Cowboy Trail and Chadron. Later this year, Ledbetter said, the city plans to seek bids for the first mile of the Cowboy Trail connection. This effort is supported by a $178,000 federal Recreational Trails Program grant, a matching contribution from Dawes County’s tourism board and a grant from RTC.

Meanwhile, Cowboy Trail West has helped with mowing and spraying, even sharing a steel-cut mile marker template. Ledbetter’s group raised funds by selling signage sponsorships to local businesses supporting the Cowboy Trail.

While that progresses, Ledbetter and a few cyclists cut a temporary path with permission from Nebraska Northwestern Railroad. “We bought a string trimmer, and we went out and mowed a path, and we’re doing a weekly Saturday morning ride,” he said. By the end of summer, they think they’ll have a usable mountain bike connector all the way to the start of the official Cowboy Trail to tide them over.

“It’s kind of like we’re out here in the middle of nowhere,” he reasoned. “So, let’s just do it ourselves.”

This article was originally published in the Fall 2025 issue of Rails to Trails magazine and has been reposted here in an edited format. Subscribe to read more articles about remarkable trails while also supporting our work.

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.