The Big Burn: Exploring the Great Fire of 1910 in Idaho and Montana

The 1910 Wildfires That Ravaged the American Northwest and Shaped the Forest Service

As summer began, it was evident that trouble was smoldering in the Bitterroot Mountains of Idaho’s panhandle. The driest year in memory, the winter’s snowpack had melted early, and life-sustaining spring rains never fell. By August, what should have been swift-running rivers cascading down the northern Rocky Mountains were ghosts of their former selves, and many smaller creeks had simply ceased to exist, vanishing into the parched earth below. By late summer, some 9,000 firefighters were already at work trying to tamp out fires flaring up across millions of acres of kiln-dry forest. The Great Fire of 1910 was nigh.

No single ignition source was responsible for what is estimated to be as many as 3,000 individual fires of varying size that merged into a deadly conflagration considered, if not the largest, certainly the most consequential, forest fire in U.S. history. Many flare-ups were sparked by the same mechanism since time immemorial: lightning arcing downward from rainless thunderstorms. But others were very much manmade—campfires set by miners, loggers and homesteaders that grew out of control, and by embers thrown off by wood- and coal-powered locomotives along hundreds of miles of tracks that pierced the forested landscape.

Strong Palouse winds blew into the Bitterroots on Aug. 20, combining the innumerable smaller fires into bigger and stronger blazes. As the fires merged and grew, the vast amount of rising hot air drew in fresh air at gale-force speeds, intensifying the inferno in the same way that bellows feed a forge. “The flames roared over the Bitterroots with no more pause than the Clark Fork [River] over a boulder,” said Stephen Pyne, an emeritus professor at Arizona State University, TED Talks speaker and author of more than 30 books, among them “Year of the Fires,” a comprehensive look at the fires of 1910.

This article was originally published in the Spring/Summer 2025 issue of Rails to Trails magazine and has been reposted here in an extended format. Subscribe to read more articles about remarkable trails while also supporting our work.

A Red Demon From Hell

Contemporary accounts confirm the magnitude and destructive power of the event; a forester named Edward Stahl wrote of flames shooting hundreds of feet in the air, “fanned by a tornadic wind so violent that the flames flattened out ahead, swooping to earth in great darting curves, truly a veritable red demon from hell.” Thick smoke blotted out the sun, leaving the darkened landscape illuminated by violently burning trees and wind-powered fireballs that rocketed across canyons to ignite the far side in an instant. “The fire turned trees into weird torches that exploded like Roman candles,” one survivor told a reporter.

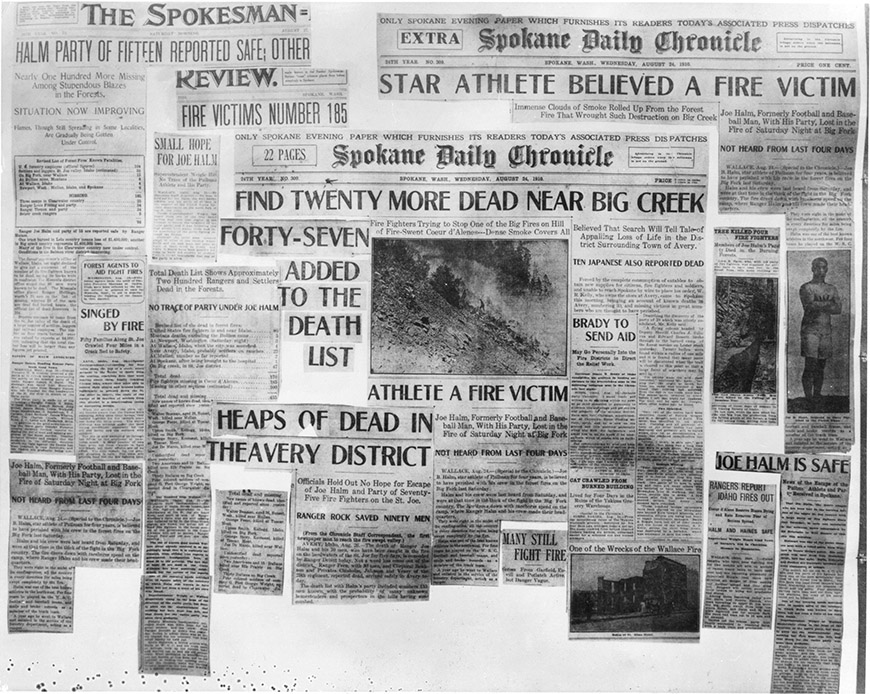

The Great Fire of 1910—also called the Great Idaho Fire, the Big Blowup and the Big Burn—ravaged northern Idaho, western Montana and parts of British Columbia. Before it was through, it claimed 87 lives—78 of them firefighters—and destroyed about a third of the town of Wallace, Idaho.

During remarks delivered at a rededication of a firefighters’ memorial in 2010, Pyne asked the audience to consider that the U.S. Forest Service had been in existence for barely five years before being tasked with taming the 1910 wildfires and had never faced fires of that magnitude. The fledgling service “rounded up whatever men it could … and shipped them into the backcountry,” he said. President Taft’s authorization of military assistance added 4,000 troops to the firefighting efforts, and the inclusion of seven companies from the U.S. Army’s 25th Infantry Regiment—the Buffalo Soldiers—was said to almost double the Black population of Idaho at the time.

“The fires of 1910 fundamentally shaped the nascent Forest Service, with ‘the memory of the fires spliced into its institutional genes.’”

—Stephen Pyne, Emeritus Professor, Arizona State University

Forged in Fire

The fires of 1910 fundamentally shaped the nascent Forest Service, with “the memory of the fires spliced into its institutional genes,” said Pyne. More than just another natural disaster, “the Big Blowup is the creation story for the American way of wildland firefighting.”

Indeed, three months later, an associate district forester named Ferdinand Augustus Silcox wrote that the lesson of the fires was that they were wholly preventable; all it took was more money, more men, more trails, more will. Twenty-five years later as chief of the Forest Service, he was able to put this philosophy into practice, implementing what became known as the 10 a.m. policy: the goal that every fire should be controlled by 10 o’clock the morning after initially being spotted.

Alyssa Kreikemeier, an assistant professor of environmental history at the University of Idaho, agrees that the 1910 fires were the beginning of a focus on combating fires—the idea that there’s no such thing as a good wildfire—that came to dominate the federal government’s approach. “That’s the moment where suppression [becomes] the primary goal,” she said. In the aftermath of the Great Fire of 1910, the Forest Service’s budget was doubled and the agency “built roads, lookout towers and fire breaks through areas of uninhabited forest. Patrollers used towers, automobiles and, later, airplanes to scan forests for the first sight of a flame.”

Experts today generally agree that fire is an integral part of a healthy and sustainable forest, but as Kreikemeier said, “There was no real understanding of fire ecology” at that time. She’s quick to point out that “Native Americans understood that these landscapes needed to be managed with fire” and there were certainly some experts at the time arguing against stamping out every wildfire, but these viewpoints were on the losing side of a fire-suppression-at-all-costs philosophy that dominated for decades.

While effective in the short term at preventing significant fires, the Forest Service ultimately came to understand that the policy actually resulted in an ever-increasing fuel load that built up year after year, with devastating consequences. As Pyne put it, “Every urban fire put out is a problem solved; most wildfires put out are problems put off.”

Today, the Forest Service takes an approach in which fire is suppressed but also managed to play its role in nature.

Big Ed Pulaski

“Very little about the Big Blowup is clear,” wrote Pyne in his book “Year of Fires.” He continued, “Facts vanished like pine needles in the firewhirls. Accounts written a year or even 30 years afterward are full of events forgotten, suppressed, embellished. Probably nowhere is that truer than with the Pulaski saga.”

While many the minute-by-minute accounts of bravery and heroism were lost in the metaphorical and quite literal haze of the fires, this much is certain: Edward Pulaski was only two years into his job as a forest ranger, but knew his way around the great outdoors, having worked on railroads and as a ranch foreman and miner. He was supervising a fire control crew south of Wallace on Aug. 20 when the fires quickly flared out of control.

Realizing that death was racing toward them, he led a miles-long dash to safety, picking up stragglers along the way who had been separated from their own crews. Eventually, Pulaski and the 45 men he was leading found themselves surrounded by flames and left with no option but retreat into a narrow, abandoned prospector’s mine some 80 feet long and barely tall enough to stand upright. Inside, said Pyne, “it was a crowded, fetid, dark place.” Outside, an inferno raged and filled what little refuge they had with choking smoke.

Pulaski worked desperately to keep the timbers supporting the adit entrance—the horizontal passage leading into the mine—from burning and bringing the whole tunnel down on their heads; he doused the supporting braces with hatfuls of water from a minuscule stream seeping through the mine and used horse blankets to smother any flames. Today, the deeply charred remains of the thick adit timbers can still be seen.

Even underground, the force of the fire was extreme; the group’s two horses died from smoke inhalation, and Pulaski himself was burned and suffered eye and lung damage from the heat and smoke. One of the men announced his intention to brave the flames outside the mine. “There in a murky silhouette against the flames,” wrote Pyne, “he met Big Ed Pulaski, pistol in hand, who said he would shoot the first man who tried to leave.”

One firefighter had fallen behind in the mad flight to the mine, and five more died in the adit itself, but all told, Pulaski is credited with saving the lives of 39 men. While hailed as a hero, Pulaski himself rejected the appellation, didn’t seek publicity, and committed his recollection of the events to paper only 13 years after the fact—and this, explained Pyne, was only at his wife’s insistence to help pay for eye surgery he received to overcome injuries sustained in the adit.

Despite that, his name lives on in the iconic tool generally called a Pulaski. While the man himself did not invent the combination of axe and adze with which a firefighter could chop trees and dig firebreaks with the same tool, he refined, promoted and popularized the design. His original prototype is on display at the Wallace District Mining Museum, and today, the Pulaski is symbolic of wildfire fighting efforts.

Remembering the 1910 Firefighters

Spanning nearly the entirety of Idaho’s panhandle, the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes is a segment on the country-spanning Great American Rail-Trail®. It traverses 73 paved miles through scenic mountains, valleys and prairie, and crosses a broad lake on the 4,000-foot-long Chatcolet Bridge. As the trail approaches the Montana border, it skirts the small town of Wallace (population around 800), of which nearly a third was lost in the Big Burn.

Turn off the trail into town at the Historic Wallace trailhead to visit the Northern Pacific Depot museum (open seasonally) and the Wallace District Mining Museum. On the south side of town along the lightly trafficked Placer Creek Road is the trailhead for the Pulaski Tunnel Trail, a 4-mile out-and-back hike that takes visitors along the route that Pulaski’s crew followed in their flight from the fire and ends overlooking the charred timbers supporting the adit where they sought shelter.

Both the route and tunnel are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and fittingly, some interpretive signage along the route is flanked by Pulaski firefighting tools. Hikers, please note that the trip is considered somewhat arduous and should take two to three hours to complete the round trip.

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.