Route of the Badger

Group bike ride in Milwaukee, Wisconsin | Video still courtesy Johnson Media Consulting

Vision | Reconnecting Milwaukee | Map | Benefits | Resources

Vision

Creating Healthier Communities in Wisconsin

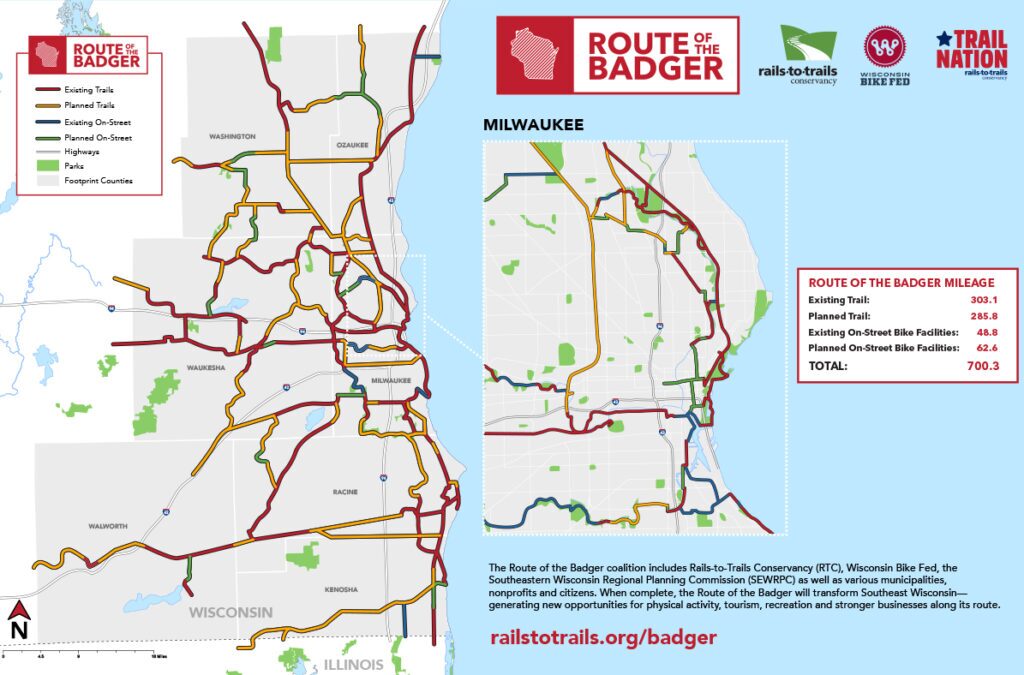

The Route of the Badger offers a vision of healthy, thriving communities in Southeast Wisconsin centered around a world-class, 700-miles-plus regional trail system that connects people across towns and counties, providing endless transformational opportunities for physical activity, tourism, connections to nature, recreation and stronger businesses along the route.

Southeast Wisconsin is home to 340 miles of existing trails. A relatively small investment that builds upon existing infrastructure can greatly improve connectivity regionwide—better connecting people to the places they want and need to go.

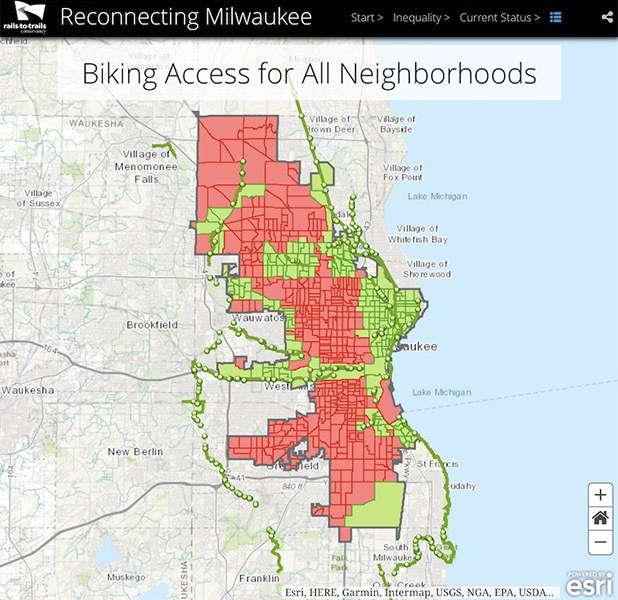

Reconnecting Milwaukee

A BikeAble™ Study of Opportunity, Equity and Connectivity

Milwaukee’s exemplary trails, including the Oak Leaf Trail and Hank Aaron Trail, serve as critical infrastructure for city residents, connecting communities and offering transportation and recreation benefits to those who use them. But the benefits that trails bring are not equitably shared among the residents who live there.

A new RTC study finds that neighborhoods experiencing inequality in Milwaukee—those where a concentration of the population lives under the poverty line, is unemployed, does not have a high school degree, does not own a vehicle and is either African American or Hispanic—disproportionately lack access to biking and walking facilities. The study, Reconnecting Milwaukee—A BikeAble™ Study of Opportunity, Equity and Connectivity, explores current access for bicyclists and pedestrians to employment centers and schools as well the impact that potential plans for new trails and biking facilities could have on the city.

Route of the Badger Footprint

While the current Route of the Badger project sections are still under planning—the following summarize the potential north-south, east-west and loop corridors and segments—many of which are already completed—that could connect the seven-county region.

Milwaukee County to Waukesha County (East-West Corridor)

The well-used 13-mile Hank Aaron State Trail running through the heart of Milwaukee could unite in Waukesha to the 51.6-mile Glacial Drumlin State Trail (via the New Berlin Recreation Trail), which extends to Greater Madison. This would create a long-distance connection of 70-miles-plus that supports bike tourism and creates economic development opportunities between Wisconsin’s capital and largest city.

This route connects to the 116.7-mile Oak Leaf Trail, which will form two connected loops throughout Milwaukee County.

Milwaukee: 30th Street Corridor

Central to the Badger route is the 30th Street Greenway Corridor trail project, which—traveling through some of the poorest neighborhoods in Milwaukee—would help address many disparities by providing increased opportunities for public transit, active transportation and recreation, and help support economic development along the route.

In the planning phases for many years, the trail would be developed along an active segment of north-south rail line beginning near the Hank Aaron State Trail and heading north past the MillerCoors Brewing Company for 3.5 miles to Havenwoods State Forest.

RTC is committed to helping explore and create these connections—as well as generating crucial support from the surrounding communities to ensure the project is a success.

Racine County to Milwaukee County (Southeast Corridor)

RTC is working to create a 75-mile destination trail in Milwaukee and Racine County. Initially, RTC is helping to facilitate the acquisition of a disused 12-mile section of the Canadian Pacific Railway, which connects to the White River State Trail. With the successful addition of this important corridor, there will be gap filling between Racine, Union Grove and Burlington—to Milwaukee in the north and back to Racine—creating the 75-mile loop.

Milwaukee County to Ozaukee County (North-South Corridor)

Via the Sheboygan Interurban and Ozaukee Interurban rail-trails, the project route connects Sheboygan to Mequon just north of Milwaukee.

Completing gaps in the trails running south along Lake Michigan in areas such as Kenosha and Racine could expand the Badger’s reach as far south as Chicago—a north-south distance of almost a hundred miles. This would create an interstate trail tourism route between Milwaukee and Chicago, one of the most bike-friendly cities in the U.S.

Stories from the Route of the Badger

View More Blogs

TrailNation in Action: Creating Lasting Impact in 2024

Reconnecting Communities Program Elevates Role of Trail Networks in Revitalizing Communities

Federal Grant Boosts Trail Connectivity Within Milwaukee’s 30th Street Corridor: A Model for Collaborative Community Development

Route of the Badger in the news:

- Momentum builds for the 30th Street Corridor bike trail as leaders hope to end ‘trail desert’ on north side | NBC TMJ4 Milwaukee

- Soul Roll MKE is underway, with bike ride to support proposed trail through north side of Milwaukee | NPR WUWM

- Greenfield gets a $1.2 million boost to build new Powerline recreational trail | Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

What This Means for Wisconsin

The Route of the Badger has the potential to transform Southeast Wisconsin’s trails into a 700-miles-plus premier trail network, sparking new waves of outdoor tourism, spurring economic development, promoting healthier lifestyles and bridging gaps in communities for a more socially equitable and vibrant region.

Expanding Transportation Options

In Milwaukee, as many as one in five residents do not own a car, which means their transportation options are limited. With access to a connected regional trail system, they’ll have more active transportation options that safely and conveniently connect them—and others across the region—with the places they want and need to go. The Route of the Badger will integrate with Wisconsin’s burgeoning multimodal transportation system, creating safe routes to everywhere for everyone, regardless of age, race and income.

Fueling Strong Economies

The economic impact of bicycle recreation and tourism in Wisconsin is more than $900 million each year. Vibrant regional trail systems are proven economic drivers, sparking neighborhood-scale economic development with tourism, new investment in trailside businesses and commercial opportunities along trail routes.

Improving Health and Wellness

When people have access to safe places to walk within 10 minutes of their home, they are one and a half times more likely to meet recommended activity levels than those who don’t. The Route of the Badger will give people living in Southeast Wisconsin new access to outdoor recreation, with the potential for increased physical activity and a savings in direct health-care costs of more than $22.4 million.

Enhancing Regional Competitiveness

Quality of place is a key factor in attracting and retaining a younger, highly educated workforce, and trails add value; millennials walk, bike and take public transportation significantly more than people their age did a decade ago, and nearly 80 percent of those living in large cities say they get around on foot. The Route of the Badger will expand on this value and help the region become a talent magnet.

Promoting Social Equity

Milwaukee is one of the most racially segregated cities in the U.S.—and just like with other forms of infrastructure, disparities exist in the distribution of trail and active transportation networks. For example, in urban Milwaukee, where many residents are living in poverty or in extreme-poverty areas with limited access to public transit, it is difficult or impossible to travel to suburban job centers or reach other non-urban destinations, including schools, shopping areas and health-care facilities. If done thoughtfully and with meaningful community engagement, comprehensive trail systems can bridge gaps within and between communities, providing access to safe transportation, physical activity and outdoor recreation, and improving health and quality of life. See how the 30th Street Corridor trail project will move the dial toward active transportation equity in Milwaukee.

Route of the Badger History

In development since 2014, the Route of the Badger was conceived by RTC after an analysis revealed that in the Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis-Racine metropolitan area, 90 percent of the population lived within 3 miles of a trail.

The region—which has 340 miles of trails on the ground—was recognized as an ideal potential model for the next step in trail development: making small investments in trail infrastructure to leverage these larger (completed) investments—thereby creating benefits bigger than the sum of their parts related to health, economic development and tourism, conservation, walkability and bikeability.

On Sept. 14, 2016, RTC and Wisconsin Bike Fed unveiled the project to 100 potential partners at the Johnson Foundation at Wingspread in Racine, with presentations by RTC President Keith Laughlin, Wisconsin Bike Fed Executive Director Dave Cieslewicz, Racine County Executive Jonathan Delagrave and Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Hank Aaron State Trail Manager Melissa Cook.

Building on that momentum, an official kick-off meeting for the project took place on Nov. 30, 2016, with more than 60 people in attendance.

Moving Forward

The Route of the Badger partner network has embarked on the first phase of the project (2016–2017). This is an exciting time, as the groundwork is being established to create a strategic initiative to complete the gap-filling strategy. The first step the partner network established was to focus on four working groups to accomplish the separate yet over-lapping goals of the Badger.

The working groups include: 1) Governance 2) Economic Development and Tourism 3) Public Outreach and Communication 4) Mapping and Trail Network Planning. The partners will convene four quarterly meetings for all four working groups to help establish a collaborative design phase to: identify the trail gaps; determine which gaps would add the highest value if filled; and develop strategies for completing the work. Tools that will assist the working groups include Bikeable analysis.

An early focus of the project is to close gaps in the trail network between urban and suburban neighborhoods in Milwaukee, Waukesha and Racine counties to develop a 75-mile trail loop connecting Racine and small towns to the west and Milwaukee to the north.

Partners

The Route of the Badger is a partnership of the Wisconsin Bike Fed and RTC to build healthier communities across Southeast Wisconsin.

To build regional momentum for the project, the partners continue to seek and develop relationships with many different stakeholders, including local governments, trail managers, biking groups, friends groups, nonprofits and the public.

Resources

Contact

Wisconsin Field Office

187 E Becher Street, Milwaukee, WI 53207