Kentucky’s Louisville Loop

Trail of the Month: February 2018

“It’s pretty exciting to think of a continuous loop that traverses the entire city.”

Louisvillians officially named the Louisville Loop in 2005, but you could argue that trails run in this city’s lifeblood. In the 1890s, pre-eminent landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. envisioned large community parks connected to the neighborhoods of Louisville via “ribbons of green.” His tree-lined parkways still exist today and will serve as spokes to the 100-miles-plus Loop, once complete.

“Olmsted was all about providing an experience for people in the community that was uplifting, restful, restorative and recreative,” explained John A. Swintosky, senior landscape architect with Louisville Metro Division of Transportation. Swintosky, who was formerly on Louisville Parks & Recreation Department staff when he became a Louisville Loop project manager, has been working alongside transportation planner Milana Boz on the project for a long time; he jokingly added that they’ve “been in it since dirt.”

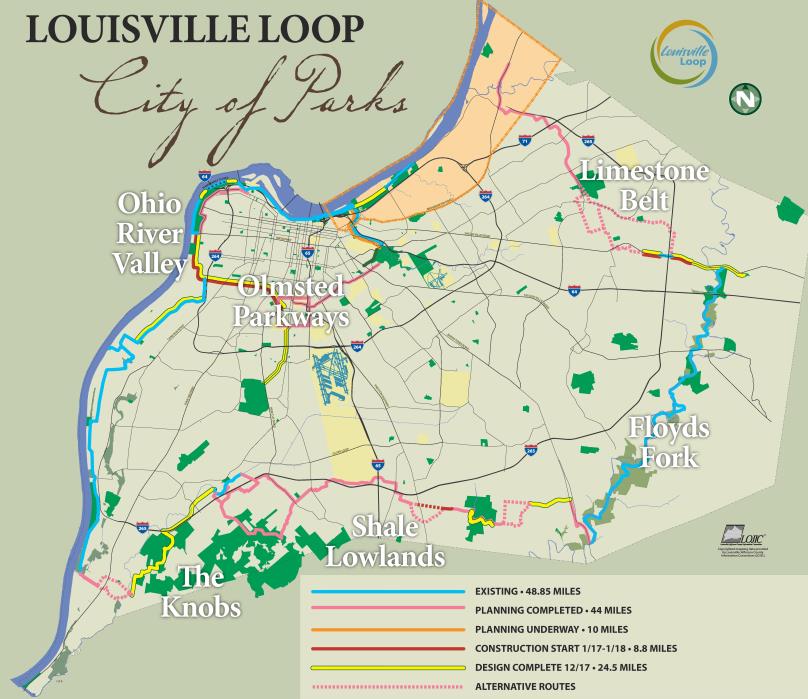

The planned Loop will take trail users through five parts of Jefferson County, giving them a taste of each section’s unique heritage, character and physiographic attributes. As of recently, all five segments have been planned out, with nearly 50 miles completed and various sections in design or construction.

From Concept to Case Study

From the start, the city has considered the Loop an essential part of Louisville’s transformation into one of the nation’s most livable cities. The Loop’s estimated impact on the city’s economic growth, connectivity and health are just a few reasons Rails-to-Trails Conservancy (RTC) reached out to the Louisville Metro Parks and Recreation Department (Metro Parks) about the project in 2017.

RTC now points to the Loop as a model of how communities are using active-transportation infrastructure development to address economic, transportation and health goals—with the project serving as a case study in its “Trails Transform America” campaign to ensure trails and walking and biking networks are included in federal infrastructure legislation.

Louisville officials are particularly encouraged by national studies showing the rise of property values close to trails, including the Little Miami Scenic Trail in nearby Cincinnati. The finished Loop will be within: 1 mile of 66 percent of residents, 0.5 mile of 94 percent of bus routes and 1 mile of 42 percent of public schools. It also connects to some of the city’s largest employment centers. In addition to creating an estimated 969 jobs, the Loop is expected to attract new business to the region and inspire more outdoor tourism. In 2017 alone, the Parklands of Floyds Fork, through which the Loop runs, saw more than 3 million visits.

“Louisville is such a great example for the country because it’s not a New York City or San Francisco—it’s Middle America,” stated Leeann Sinpatanasakul, RTC’s advocacy manager. “If Louisville can build a 100-mile trail system, anyone can.”

Over the River and Through the Woods

Metro Parks designed each of the Loop’s five sections—Ohio River Valley, the Knobs, Shale Lowlands, Limestone Belt and Floyds Fork—to display their distinct charms, while a cohesive wayfinding and interpretive signage system funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2010 ensures visual consistency throughout the network.

“It’s pretty exciting to think of a continuous loop that traverses the entire city and county,” said Erika Nelson, Metro Parks community relations administrator.

Mile 0 kicks off the Loop’s largest continuous section: the 25-mile Ohio River Valley segment. Heading west from the Big Four Bridge, visitors can soak up all that the downtown Riverwalk Trail has to offer, from public art installations at Waterfront Park to the Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory, and Olmsted’s Shawnee and Chickasaw Parks.

The off-road Levee Trail picks up from the Riverwalk, providing users with a diverse mix of vistas, as lifetime Louisville resident and Louisville Bicycle Club President Andy Murphy can attest. Every Thursday, he leads around 50 riders down this segment and back.

“On that Thursday morning ride, we get to see downtown, then we see the old architecture of houses in the West End, and then we get out to the more industrial part of the city, Riverport, and 5-acre tracts where people have horses. It’s really a neat little part of the world,” Murphy said.

Heading east from the river, the Knobs and Shale Lowlands will no doubt become a haven for adventurous hikers, geologists and nature enthusiasts. These segments will traverse one of the county’s most geographically diverse regions, featuring farmland, ancient lake beds and the 6,600-acre Jefferson Memorial Forest. The developing Limestone Belt South region boasts sights of limestone bedrock, the nearly 40-foot Fairmount Falls and McNeely Lake Park, a future focal point of the Loop.

Parklands of Floyds Fork

Undoubtedly the biggest development over the last decade has been the completion of the Parklands of Floyds Fork segment. This well-loved, 19-mile, off-road portion of the Loop follows the nearly 4,000-acre Parklands along its north-south corridor and lives up to its name, encompassing no fewer than four parks. From Broad Run Park in the south (near mile 55 of the Loop’s planned 111 miles) all the way up to Beckley Creek Park (mile 74), the Parklands segment provides adventurers with everything from canoeing and kayaking along Floyds Fork to mountain biking at Turkey Run Park’s Silo Center Bike Park.

At Trestle Point in Pope Lick Park, historians and rail enthusiasts will appreciate that the Loop passes directly under a late 1880s train trestle, where local lore alleges that a “Pope Lick Monster” resides. At the Strand, nature lovers can observe wildlife at Catfish Bend, while archaeology buffs can search for fossils deposited on the gravel bars of Mussel Bend. Trails and educational opportunities abound throughout this must-see destination that’s only a 20-minute drive from downtown Louisville.

Completing the Loop will be the suburban Limestone Belt Northeast, which will pick up from the northern tip of the Parklands and loop west to the city of Prospect and the Ohio River Valley Northeast. Extending the Loop to these more suburban areas is the next big hurdle for the trail’s designers. Though Metro Parks staff acknowledge this won’t be an easy feat, they can rely on the community for continued engagement with the Loop’s progress.

“The Loop encompasses every area of our community and our city,” stated Nelson. “That’s an easy way to keep people engaged and involved. They stay excited because they know it’s getting closer to them, and they’re seeing headway.”

Full-Circle Connectivity

The Louisville Loop is already living up to its goal of linking people to places and each other. The dynamic project has brought together not only trail users, but also a vast network of partners making the work possible.

“There’s value in being collaborative in your approach,” affirmed Swintosky, recalling how the CDC recognized the Loop’s potential to promote active lifestyles and decrease long-term health-care costs. Such efforts are bearing fruit in people such as Murphy, who has been riding with the club since the day he retired in 2007 and is determined to lead a more car-free lifestyle, partly due to health reasons.

“Life looks a little different from the seat of a bicycle,” he stated. “My wife and I live in the city, so I can be just about anywhere in 15 to 20 minutes on my bike.”

In addition to leading the 50-mile-roundtrip Thursday morning rides for bike club members, many of whom are fellow retirees, Murphy helps lead new-rider clinics in inner city areas. On a weekly basis, he witnesses non-experienced bikers transform into confident trail riders. Such victories exemplify what the city is seeking on a large scale, harkening back to Olmsted’s legacy of connecting people to trails.

RELATED: How to Prepare for Your First Long-Distance Trail Ride

Representing so much more than a recreational path, the Louisville Loop is addressing the quality of life, prosperity and connectivity of its community, making it a powerful example of how active transportation networks deserve a place in the federal infrastructure discussion.

Related Links

City of Louisville

Trails Transform America Case Study

Parklands of Floyds Fork

Trail Facts

Name: Louisville Loop

Trail website: City of Louisville

Length: Nearly 50 constructed, though not contiguous, miles. The largest continuous section along the Ohio River Valley starts at mile 0 at the Big Four Bridge downtown and continues to the Watson Lane trailhead in southwest Louisville at mile 25.25. The next-longest section is the 19-mile stretch contained within the Parklands of Floyds Fork. After that, there are 1.5 miles along Pond Creek from west of Lamborne Boulevard to West Manslick Road; 0.25 mile in McNeely Lake Park at Cedar Creek Road; 0.6 mile along US 60/Shelbyville Road at I-265; 1.2 miles along River Road from Zorn Avenue to Caperton Swamp; and 0.9 mile along River Road from the Big Four Bridge to Beargrass Creek.

County: Jefferson

Start point/end point: The Big Four Bridge in Waterfront Park on the Ohio River downtown is the official mile marker 0. The trail then proceeds counterclockwise around the community. Current end points of the Ohio River Valley segment are the Big Four Bridge in Waterfront Park to Watson Lane near the Mill Creek Generating Plant. End points of the completed Parklands of Floyds Fork segment are Broad Run Park to Beckley Creek Park.

Surface type: The Louisville Loop is primarily asphalt pavement, with some concrete sections in the Parklands of Floyds Fork and in urban neighborhoods along existing streets.

Grade: Generally, the Louisville Loop maintains no more than a 5 percent slope, though it traverses certain areas of more challenging terrain in the Parklands. The Loop is built along the top of the Ohio River flood levee structure and follows street and highway rights-of-way for significant distances.

Uses: Finished sections of the Loop are popular among cyclists, walkers, runners and inline skaters. The majority of the existing Loop is wheelchair accessible, though the Loop traverses certain areas of steeper terrain in the Parklands. In two distinct corridors that currently contain only bike lanes (miles 8.25-10.0 and 10.75-13.75), Louisville Metro Government will be implementing off-road bicycle and pedestrian facilities over the next few years. Mountain bikers can also enjoy Silo Center Bike Park, located within the Parklands’ Turkey Run Park.

Difficulty: The majority of the existing Louisville Loop features flat-level grades with occasional short stretches where the slope may reach 5 percent. The 25 continuous miles from the Big Four Bridge out to the Watson Lane trailhead has been described as “pan-flat,” making for an easy walk or ride. In the Parklands segment, however, there are some places with more challenging hilly terrain.

Getting there: Louisville International Airport (600 Terminal Drive, Louisville, KY) is located about 15 miles from the Big Four Bridge in Waterfront Park and about 19 miles from Broad Run Park in the Parklands.

Access and parking: In the Ohio River Valley segment, parking is available in many of the parks along the route, including (from north to south): Caperton Swamp, Carrie Gaulbert Cox, Eva Bandman, Waterfront, Lannan, Shawnee, Chickasaw, Riverside Gardens and Riverview. Other trailheads and/or parking lots along include Mike Linnig’s Restaurant; Riverside, The Farnsley-Moreman Landing; and Watson Lane at Mill Creek Generating Plant.

In the Parklands of Floyds Fork segment, visitors can access numerous trailheads and parking lots throughout the Parklands’ four parks. For more info, visit: theparklands.org/directions.html.

Parking along other developed parts of the Loop include the Lamborne Boulevard and West Manslick Road trailheads at Pond Creek, as well as the McNeely Lake Park trailhead at Cedar Creek Road.

To navigate the area with an interactive GIS map, and to see more photos, user reviews and ratings, plus loads of other trip-planning information, visit TrailLink.com, RTC’s free trail-finder website.

Rentals: Louisville’s bike share program, LouVelo, has downtown facilities featuring bike rentals ranging from pay-as-you-go to monthly passes. Wheel Fun Rentals (502.589.2453), located near the Big Four Bridge at Waterfront Park (Red Lot), offers hybrid, cruiser, tandem and children’s bike rentals from March to November. Depending on the model, bikes are available for rent by the hour, half-day or full day. Parklands of Floyds Fork visitors can rent bikes from Blue Moon Canoe & Kayak of Kentucky (502.753.9942), the exclusive canoe, kayak and bike outfitters for the Parklands. Blue Moon Canoe & Kayak of Kentucky is located at the John Floyd Community Building within the Parklands’ Pope Lick Park and offers bike rentals, weather permitting, April through October.

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.