Saving America’s Prairies: Illinois Leaders and Rail-Trail Advocates Work to Restore a Dwindling System

From a distance, the flowers and grasses growing alongside the old highways and roads in East Central Illinois can look remarkably like dense stands of nuisance weeds. But those who take the time to stop and get out of their car for a closer look will be rewarded with bursts of color and a variety of leaf shapes and sizes from hundreds of species of wildflowers and tallgrasses—some that can tower up to eight feet.

These are the remnants of the tallgrass prairies that once covered more than 60% of the state and now stand at less than a tenth of 1 percent of their original distribution. In fact, tallgrass prairie is one of the most depleted ecosystems in the world.

In Illinois, a good portion of what remains is found almost exclusively along the railroad corridors that crisscross swaths of intensely farmed, highly prized agricultural land. When settlers first arrived, farmers considered the prairie land a nuisance with its insects, its alternating wet and dry seasons, and its plants boasting taproots dozens of feet deep and several inches wide.

By the early 1800s, they realized that the prairies were among the most fertile agricultural lands in the world. And by then they had the tools they needed to drain the wetlands and cut through the dense prairie sod. So began the removal of the prairies in the Midwest to make way for agriculture—particularly corn and soybean farms—which now dominates the state.

Local trail developers and conservationists have recognized the potential to convert the corridors in their midst to multiuse trails, and thus, they hope to permanently protect a disappearing natural treasure—tallgrass prairies. Unused railroad corridors have been purchased, trail plans have been made, and long-nurtured dreams have begun to unfurl. The battle is ongoing, however, and fingers are crossed as one rail-trail is poised to break ground, funding is sought to make another project a reality, and potential interconnecting corridors are eyed for the future.

A Hope and a Dream

Most people think of rail-trails as places for transportation, recreation or community activities. But these trails often provide tangible, measurable environmental benefits that are less obvious to typical trail users, such as improved water quality in adjacent streams and rivers, habitat preservation and creation of wildlife corridors, and mitigation of the effects of climate change. In some areas, all these benefits come together in the protection of an entire ecosystem, a situation perhaps no more evident than in East Central Illinois, where, some say, the history of rail-trails really began.

“Because of their longevity, when you set aside and retain a railroad corridor, you also pull aside and retain the ecosystem associated with that corridor,” says Timothy A. Bartlett, executive director for the Urbana Park District, which is planning to develop a park with a trailhead to mark the beginning of the trail in downtown Urbana.

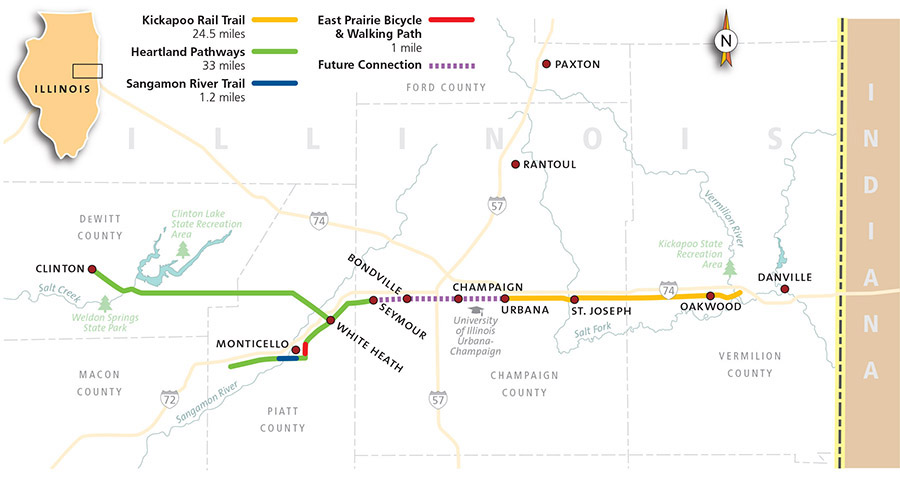

Bartlett is working on a project to create the Kickapoo Rail Trail, a 24.5-mile recreational trail linking Champaign and Vermilion counties, from Urbana on the west to Kickapoo State Park in Danville on the east. Along this trail are remnants of tallgrass prairie as well as woodlands and wetlands—diverse natural resources that used to dominate the area before agriculture took over.

Almost 20 years in the making, the Kickapoo trail project is part of a larger effort to create an interconnected regional trail network that dates back to 1988. That effort was initially championed by one man, David Monk, a preservationist, environmentalist, naturalist, educator and activist who has been working for more than 30 years to preserve the prairies of Illinois.

In 1987, Monk founded Heartland Pathways, a nonprofit organization dedicated to prairie preservation. A year later, Heartland Pathways purchased three separate segments of unused rail corridor totaling 33 miles and more than 330 acres, and encompassing many acres of valuable prairie remnants. The goal: to create the Heartland Pathways trail system and help preserve the diversity of the grasslands that used to flourish along the corridor. “At the time, it was sort of outrageous to buy 33 miles of railroad bed,” Monk says.

The Heartland Pathways trail project is located west of Champaign-Urbana, directly opposite the Kickapoo Rail Trail. The plan is eventually to connect the two, though additional corridor would need to be purchased before that could happen. “The vision is to have the two trails—the Heartland Pathways and the Kickapoo Rail Trail—connect through the cities of Urbana and Champaign,” Monk says.

According to Daniel J. Olson, executive director of the Champaign County Forest Preserve District (CCFPD), Monk was key to getting this ambitious project started. “He really is a visionary. He knew the rail line needed to be saved to protect the prairies,” Olson says. “David was instrumental in recognizing the value of this land and in getting it, and he has been working on it ever since.”

Project Status and Future

After 17 years of negotiations, the deal for the Kickapoo Rail Trail finally closed about a year ago. The Vermilion County Conservation District (VCCD) recently received a $2.1 million grant from the state of Illinois that will be used for the first phase of trail development, building a segment that will run from Oakwood to Danville in Vermilion County. Funding is being finalized for the second phase, a segment in Champaign County that will run from Urbana to St. Joseph. Planners are hoping to break ground on both phases sometime in 2016. The entire project is expected to cost approximately $10 million and be completed in six phases.

Ultimately, the Kickapoo trail will connect several small towns, which should benefit greatly from an influx of tourists and local users. In fact, two villages already are preparing: St. Joseph has added a downtown wine bar, where fundraising events have been held, and Oakwood has a “trailside” ice cream and sandwich shop that’s open for business.

According to Steve Buchtel, executive director of Trails for Illinois, a trail advocacy nonprofit, the potential for tourism in East Central Illinois is high. “The world is in love with rural Americana, but there’s no access to that for most people,” he says. “What’s really cool about trails like the Kickapoo and Heartland Pathways is that they connect to a lot of main streets and get people off the interstates.”

“We are hoping this initial development will help spark interest, support,” says Bartlett. “People will see it’s happening, and they’ll want to see it continue.” In particular, he says, project supporters are hoping that a large and spectacular trestle bridge over the Vermilion River will capture the attention and imagination of local residents. That’s one reason trail development was planned to start there.

But “the absolute first thing we did was to identify very sensitive areas, including wetland and prairie areas,” Olson says. “We did that before the engineering even began so that we could tell the engineer, ‘You’ve got to protect these areas.’” In addition, because these prairies have already been disturbed—through the initial development of the railroad corridor, farming on adjacent lands, ongoing roadwork and, sometimes, encroachment—restoration and repair will also be needed.

For his part, Monk is hoping development of the Kickapoo Rail Trail will help jumpstart development of the Heartland Pathways as well, ensuring long-term protection of that corridor. The high value of land for agricultural use makes it all the more difficult to protect, Monk explains. “Unfortunately, the northern portion of the Heartland Pathways is in jeopardy,” he says. This segment starts at White Heath and runs west for 23 miles, through Clinton Lake State Recreation Area and Weldon Springs State Park. “We have lost trails to farm pressures before,” Monk adds. “The thing is to try and convince locals of the value of trails to their communities.”

Because the Heartland Pathways deal closed before federal funding for trails was available through the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991, the project is not eligible for many of the traditional grant mechanisms used for trail development, making funding a difficult proposition. Monk is hoping that increased public support will spur local and private investment.

The southern fork of the project is further along. A small portion of trail has already been developed south of White Heath. One segment is the 1.2-mile Sangamon River Trail, which the city of Monticello leased and developed for city residents. Another segment that’s up and running is the 1-mile-long East Prairie Bicycle & Walking Path, a rail-with-trail just east of the city. And a third area, between Seymour and White Heath, has been developed by the Monticello Railway Museum, which includes more than 100 pieces of railroad equipment and excursion trains that use a former railroad line.

“We are hoping that the popularity of the Sangamon River Trail and the upcoming Kickapoo trail will help generate public interest and support,” Monk says.

Monk’s group is thinking well beyond its current holdings, however. Heartland Pathways hopes to purchase a 3-mile tract of contiguous rail corridor between Seymour and Bondville that is being considered for abandonment by the Canadian National Railroad; it could form the basis of an eventual connection with the Kickapoo. In addition, the group is eyeing the purchase of an old roadbed adjacent to an active railroad corridor north of the Heartland Pathways, to create a rail-with-trail. From a biodiversity perspective, Monk says this 15-mile section from Paxton to Rantoul is one of the best prairies left in the state.

Collaboration and Education

In addition to the CCFPD and the VCCD, many groups are collaborating on the Kickapoo Rail Trail project. The Champaign County Design & Conservation Foundation (CCDC), for example, is working to obtain private donations and individual funding to complement any state or federal funds secured by the county agencies. Bike enthusiast groups and private bicycle businesses throughout the East Central area have staged events and fundraisers to support the trails.

“It’s been quite the overall effort between several agencies here trying to preserve what little we have left,” Olson says. “It’s pretty incredible.”

Ongoing collaboration and education are critical to the project’s long-term success, Bartlett says. Education helps people understand why ecosystems like tallgrass prairies are worth protecting and helps residents to better connect with their local area. The plan for the Kickapoo is to have educational information posted along the trail that details the natural and cultural history of the area, creating a rich story. “People who know the history of the prairies and know what’s in the ground, they support protecting and restoring it,” Bartlett says.

Researchers at the nearby University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign have studied the prairies for many years, primarily through the Prairie Research Institute, a consortium of several state survey groups. In addition to regular surveys, the groups provide outreach and education on prairies. Some University of Illinois students have volunteered for trail development and maintenance activities, and others have done prairie research.

Student involvement also extends to local county schools. Schoolchildren are bused in to help plant seeds and seedlings while learning about the prairie ecosystem. In this way, they too can become stewards of the land.

County staff have been successful in showing farmers that they have shared interests and concerns, such as invasive species control, or drainage and stormwater management. “Around the Kickapoo railroad corridor, for example, farmers that have drainage issues work cooperatively with corridor managers,” Bartlett says. “That’s a win-win approach there.” Once the farmers understand the value of protecting the prairies and developing a trail, they become supporters as well.

Long-term collaboration will be needed once the trails are in place, because previously disturbed prairies require active management to preserve biological diversity and maintain an ecologically healthy ecosystem. When a prairie has been disturbed, the natural processes that originally maintained the system are reduced or eliminated. That means ongoing maintenance such as removing invasive species, performing prescribed burns, replanting and seeding, and restoring natural hydrology may need to occur.

To support ongoing restoration efforts, for the past decade native plant seeds have been collected from both abandoned and active railroad corridors. One group that has been hard at work on these efforts is Grand Prairie Friends (GPF), an all-volunteer, nonprofit conservation organization. The CCFPD also collects seeds for larger prairie restoration.

Conservation and Rail-Trail History

This level of collaboration between conservationists and trail builders isn’t always the norm. But the Heartland Pathways has its roots in the early history of Illinois trail development. According to Buchtel, the project harks back to one of the first rail-trails developed in the country, the Illinois Prairie Path.

“The rails-to-trails movement started here in Illinois,” explains Buchtel. It all began with May Theilgaard Watts, a writer and naturalist who had a vision far ahead of the time to convert out-of-service rail lines for recreational use. Watts, a Rails-to-Trails Conservancy Doppelt Family Rail-Trail Champion, staved off developers to protect 75 miles of interurban rail line so that people could see and enjoy the tallgrass prairies. “From Watts’ perspective, the reason people would walk on the trail would be to see this natural environment,” Buchtel says. “Really, the trail movement started in conservancy.”

In his work, Buchtel says he often sees a rift between conservationists and trail users. “Bringing those two groups together again is so important, because they both ultimately want the same thing.” Not only that, he says, but “research shows the more time people spend out in nature, the more open they are to conservation messaging. Then they can learn how to become good stewards of the land and can teach [others].”

Environmental Benefits of Trails

Many trail developers acknowledge that any rail-trail project can provide environmental benefits, whether intentionally as a project goal or unintentionally through the act of preservation itself. They accomplish this by protecting ribbons of greenway, which is where those environmental benefits originate. But what is it about the prairies that inspires such special dedication to environmental stewardship?

According to conservationists, it’s their complexity and the larger role they play in providing habitat for hundreds of species, improving water quality, reducing the effects of climate change and more.

“Preserving the remnants in place is extremely important due to the complexity of life and the food web that developed in prairie communities,” explains Steven R. Buck, natural areas coordinator for the Illinois Natural History Survey, a division of the Prairie Research Institute at the University of Illinois. “These remnants function not only as home to species that are not very mobile, but also as critical stopover points for species that are mobile or migratory, such as the monarch butterfly and bird species. The late-blooming flower species, the myriad of insect species and the ripening seed are all critical to many of the migrating bird species that evolved in North America,” Buck says. “All the fields of ripening corn and soybeans in this area are of little use to so many species.”

Buck says he finds it ironic that these disturbed railroad corridors—ripped up during construction—have become the least disturbed areas of prairie, a refuge for prairie plant species that have crept back in over time. “The lack of trees and minimal disturbance of the soil has allowed many prairie species to persist,” he explains. And although the railbeds are narrow, at 50 to 100 feet wide, they are in fact corridors that allow movement of plants, insects, animals and water “unlike the highly fragmented landscape” in other areas, he says. Unfortunately, the tallgrass prairies that once covered much of Illinois after thousands of years in the making are now almost gone; the best that can be done is to try to reconstruct anew and protect what remains.

“It takes about five to 10 years for a regrowth prairie to look like a prairie. Until then, the site will look like weeds,” Monk says. “There is no room for instant gratification. Prairie plants have deep roots, and they have to establish first before the flowers arrive. Even then, the flowers are small and not showy except in numbers.” But, he adds, “We are preserving the only tallgrass prairie habitat remaining here and in much of the world.”

This article was originally published in the Winter 2016 issue of Rails to Trails magazine. It has been posted here in an edited format. Check out Heartland Pathways for the latest updates on this developing corridor.

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.