Pathway to Prosperity: Missouri’s Katy Trail Is a Beautiful Model for Commerce

This article was originally published in the Fall 2016 issue of Rails to Trails magazine. It has been republished here in an edited format.

Now in its 26th year, Missouri’s Katy Trail supports small businesses across the state and serves as a model for other rail-trail projects nationwide.

Missouri’s nickname—the “Show Me State”—reflects its residents’ prudent tendency to question unsubstantiated claims, so when early proponents of the Katy Trail began advocating for its creation in the mid-1980s, it was only natural that their assertions of increased tourism and economic prosperity met with a few skeptics. However, the trail has proved its worth several times over in the quarter-century since it opened, and it now supports more than 400,000 recreational users each year as well as dozens of communities and hundreds of small businesses statewide.

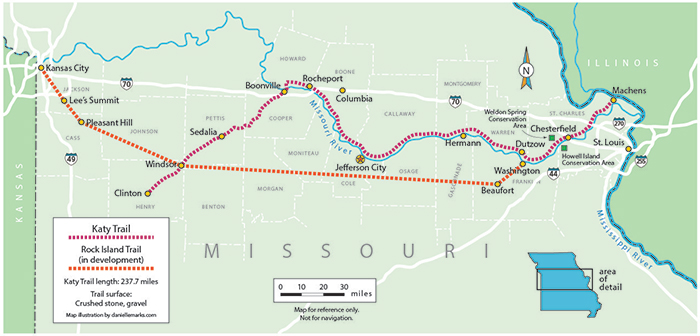

The path to prosperity hasn’t been without its bumps, and ongoing challenges demonstrate the continuing need for oversight and advocacy. Still, the 237.7-mile Katy Trail shines as one of the most robust rail-trail projects in America. In September 2007, Rails-to-Trails Conservancy (RTC) inducted it into the Rail-Trail Hall of Fame, the second of only 30 trails nationwide to receive this honor.

A Celebrated Trail

Passing through some of Missouri’s most scenic areas, it makes sense that the Katy Trail would be a popular pathway with tourists and locals. The eastern portion follows the Missouri River for 165 miles, where scenic farmland, fertile floodplains and other distinctive topographic features showcase the area’s natural history.

Along certain sections, towering limestone bluffs—documented by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark in their famous Corps of Discovery Expedition (1804–1806)—provide an otherworldly experience, and the trail segment between St. Charles and Boonville is an official portion of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

Despite featuring many landscapes—including forests, wetlands, valleys, remnant prairies and farmland—the trail is relatively flat and convenient for many types of trail use. The Katy Trail is also part of the coast-to-coast American Discovery Trail and is designated a Millennium Legacy Trail—a testament to the trail’s place in American history and culture.

The Road to Here

The Katy Trail’s name comes from the rail line that once ran along its path—the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad (MKT), first nicknamed the “K-T.” The company incorporated in 1870, bought the Southern Branch of the Union Pacific Railway that year and then began expanding from the nearly 200 miles of track in Kansas acquired as part of the deal. Over the next 100 years, the company laid more than 3,500 additional miles of track throughout Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas.

The portion of the MKT system between Boonville and St. Charles, Missouri, ran along the floodplains of the Missouri River. It suffered multiple washouts over the years that required extensive repairs. When an October 1986 flood severely damaged a portion of track along the route, the railroad decided against performing yet another repair and sought permission from the Interstate Commerce Commission (now the Surface Transportation Board) to abandon the line.

Fortunately, recent federal legislation in the form of railbanking (via an amended National Trails System Act in 1983)—in which a railroad can transfer management of a rail corridor to a recreation entity while preserving the line’s infrastructure for potential future transportation use—had paved the way for conversion of the rail corridor to a trail, opening up a new opportunity for Missourians.

The Missouri Department of Natural Resources jumped on the opportunity to acquire the Katy’s right of way and received a certificate of interim trail use in 1987—one of the first projects in the nation to benefit from the new railbanking statute. Philanthropists Ted and Pat Jones, who had lobbied the Missouri legislature for the project, donated $200,000 toward acquisition of the right-of-way and $2 million toward construction costs.

In April 1990, the first section of the trail opened up between Rocheport and McBaine. The Union Pacific Railroad, which purchased the MKT system in 1988, donated a 33-mile extension in 1991, and the state continued adding sections through 2011. Since then, expansion efforts have turned to the Rock Island Trail project, a separate rail-trail that will intersect with the Katy and significantly augment the state’s recreational offerings.

RELATED: Appalachian Engine: The Virginia Creeper Trail Keeps Bringing Visitors Back

Economic Impact

In 2012, Missouri State Parks conducted a study to determine the economic impact of Katy Trail State Park based on user spending and found the trail had a direct impact of $18.5 million per year. Roughly three dozen towns along the trail welcome trail users to their restaurants, shops, bed-and-breakfast inns and other businesses, and thousands of trail users plan mini-vacations each year that take advantage of these establishments.

While some businesses existed before the trail and have seen an uptick in revenue with the increased patronage, others specifically established their companies to cater to Katy traffic and have enjoyed significant success.

Todd White bought Katy Bike Rental in 2002 when it was just a small shop in the town of Defiance. He has since expanded the business to a $500,000-per-year enterprise with multiple locations. The Defiance location includes Robin’s Nest, a gift shop, and the Augusta store features Pop a Wheelie, an ice cream shop with drinks and other concessions. Today the business employs 30 Missourians.

“We’ve bumped up sales sixteenfold since 2002,” White says, noting the consistently high demand for his services from trail users. “My gross revenue doubled between 2013 and 2015.”

Many other businesses along the route have seen similar success based largely on their proximity to the trail. “Over a three-day weekend, we’ll get anywhere from 20 to 100 bicyclists, weather depending,” says Mike Sloan, owner of the Hermann Wurst Haus, which sits about 2 miles from the trail. “You can tell they’re from the trail by the way they’re dressed and their cleats clicking as they walk across the floor.”

Terry Heisler, owner of Augusta Brew Haus just a few steps from the trail in Augusta, attributes the bulk of his revenue to cyclists and other trail users. “We get 80 to 85 percent of our weekend business from the Katy Trail,” he says. “This place wouldn’t survive without it.”

Rock Island Connection

While the Katy Trail is groundbreaking enough on its own, the in-progress Rock Island Trail is poised to connect with it and give Missouri a rail-trail system unlike any other in North America.

The Rock Island line’s history stretches back to 1847, when the Rock Island and La Salle Railroad Co. incorporated in Illinois. During the mid-1960s, the company pursued a complicated merger with Union Pacific Railroad, and it entered its final bankruptcy in 1975. Union Pacific purchased the corridor, and as the rail line changed hands, community support emerged for a proposed trail along the Rock Island line similar to the Katy Trail.

Rock Island Trail supporters had reached a tentative agreement with Union Pacific to railbank the trail in 1993, but the Surface Transportation Board canceled that plan when outside investors bid on the corridor. In 1999, Union Pacific sold some of the trackage rights to the Missouri Central Railroad Co., a subsidiary of Ameren UE.

Members of communities along the corridor began meeting again in 2009 to renew the trail proposal. Ultimately they organized to form the nonprofit group Missouri Rock Island Trail, Inc. As grassroots momentum built, the state of Missouri acquired the rights from Ameren UE to build a trail alongside the rail line from Windsor to Pleasant Hill. This later led to Ameren UE agreeing to railbank that 47.5-mile corridor. Missouri State Parks began construction on the line in winter 2015, and it’s scheduled to be complete in December 2016.

At Windsor, the Rock Island Trail will connect with the Katy Trail, lengthening the continuous passage for trail users almost the whole way to Kansas City. Further west along the Rock Island line, Jackson County recently purchased from Union Pacific 17.7 miles of line, stretching from Arrowhead Stadium in Kansas City, Missouri, to Lee’s Summit. The county expects to complete trail construction on this portion by spring 2018. A 7-mile gap will remain between Lee’s Summit and Pleasant Hill; Missouri State Parks, the city of Pleasant Hill and Jackson County have vowed to complete that trail section.

East of Windsor, the Rock Island Trail’s greater potential emerges, and recent developments foretell a promising future. The corridor crosses the Katy Trail at Windsor and then continues east for another 144 miles, where it approaches the Katy again near the Beaufort/Washington area. Following a massive community effort involving leadership from RTC, Ameren UE agreed to railbank this segment and expects to turn over the corridor to Missouri State Parks by late next year.

Development of this segment will likely take several decades, but once it’s complete and the connection to the Katy Trail has been established, Missouri will have a rail-trail loop with spurs covering more than 450 miles and connecting Kansas City and St. Louis on opposite sides of the state.

Project Spotlight: Boonville Bridge

Much of the Katy Trail’s purpose is to keep the state’s history alive, and in Boonville, the Katy Bridge Coalition has worked hard to do just that. The Missouri-Kansas-Texas (MKT) Railroad built the bridge across the Missouri River in 1932. It featured a 408-foot lift span, which at the time was the longest of its kind in the U.S. The bridge carried rail traffic until 1986, when the MKT Railroad ceased operations, and in 1987 it became part of the Katy Trail railbanking agreement.

Although the Katy Trail was routed over the adjacent Highway 40 bridge, keeping the original railroad bridge intact was critical to preservation of the Katy Trail because it kept the railbanked corridor legally intact. In 2004, the Coast Guard deemed the railroad bridge a navigation hazard and instructed owner Union Pacific Railroad to demolish it. The railroad began planning to dismantle the bridge and reuse its steel on another bridge project downstream across the Osage River.

In 2009, after a long and protracted battle between trail advocates, the state and Union Pacific, Gov. Jay Nixon (then attorney general) helped save the bridge by allocating federal stimulus money for the Osage River Bridge, eliminating the motivation to dismantle the one in Boonville.

Since then, the Katy Bridge Coalition has continued to raise funds toward its renovation. The first section on the south side of the river opened in April 2016.

Continuing Challenges

Like many rail-trail projects, the Katy Trail had early opponents among rural residents who thought the trail would bring crime and other problems to their homes, farms and communities. But the economic benefits brought by the Katy combined with the near-absence of any mischief has changed people’s minds.

“There was a lot of social upheaval and opposition at first,” says Missouri State Parks Director Bill Bryan, who worked as a lawyer on Katy Trail property compensation litigation during the railbanking process. “Farmers parked their tractors on the line to block us at the time, but those same people see the economic and recreation and lifestyle benefits now. One of the most ardent [former] opponents of the Katy Trail stood up in a meeting about the Rock Island proposals and told folks who live along that line that 99 percent of people on the Katy Trail are good people. No one’s stealing watermelons or leaving litter like they feared.”

Still, challenges come up from time to time that threaten the Katy’s future. One state legislator recently proposed a bill to allow all-terrain vehicles and golf carts on the Katy Trail. The same legislator proposed another bill that would require cyclists to attach a 15-foot-tall pole with an orange flag to their bikes before operating on county roads, many of which feed into the trail. Jodi Devonshire, co-owner of the Bike Stop Café & Outpost in St. Charles, wrote in an April post on the Missouri Bicycle and Pedestrian Federation website, “We’ve had … folks telling us they will not make a vacation trip for fear of running into ATVs or the unfavorable trail conditions they will likely cause.” Both bills failed to make it out of the House, but challenges continue to surface.

Model for Others

As one of the nation’s earliest railbanking projects, the Katy Trail has been studied extensively by rail-trail proponents around the country who wish to repeat its success. Recently, a group from the Arkansas Parks and Tourism Department came to visit the Katy Trail as they consider an 87-mile rail-trail project of their own along the Mississippi River. Kansas sent a delegation last year to take notes for a rail-trail conversion that may one day connect with Missouri’s system in Kansas City.

“They came because the Katy Trail is in the RTC Hall of Fame, and there’s a great opportunity here to understand what it takes,” Bryan says of the Arkansas visitors. “When they left, we asked if they had any feedback for us, and they said this is exactly what they want to do.”

Former Columbia Mayor Darwin Hindman says, “The Katy Trail should be seen as a teacher, and as an example of serendipity.” Hindman, whose 20-plus years of advocacy for the trail earned him a Doppelt Family Rail-Trail Champion Award from RTC, explains, “If you do something that reaches as many people in a positive way as the Katy Trail does, good things are going to follow. You may not know what they will be, but good things are going to follow.”

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.