2020 Vision: New York’s “Empire State Trail” Is Making Trails a Main Attraction

The new 750-mile Empire State Trail project will tie together hundreds of communities across 27 counties—in the fourth-most-populous state in the nation.

To learn how the Empire State Trail and other trail networks around the country are transforming their communities through economic development, job creation, active transportation and health, go to RTC’s Trails Transform America website.

As the country’s most populous city and a hub of commerce, fashion, theater, art and entertainment, there’s not much one can’t do in New York City. Dine at five-star restaurants? Check. See world-class Broadway shows? Double-check. Begin a trek across the length and breadth of the Empire State, almost entirely along trails? Soon!

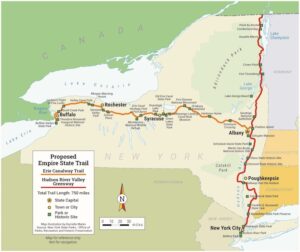

New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo announced in early January 2017 his $200 million plan to lay down 350 miles of new trails in three years to bridge the gaps in two major existing routes—the east-west Erie Canalway Trail and the north-south Hudson River Valley Greenway—and knit them together into the greater Empire State Trail (EST). Shaped like a giant sideways T intersecting near Albany, the EST will connect three corners of the state: Manhattan, Buffalo and the Canadian border near Lake Champlain.

“We want to build the largest multiuse trail in the nation,” said Cuomo at the project’s unveiling. At a total of 750 miles, the EST would become just that, easily eclipsing all other contenders.

“We’re over the moon about it,” says Robin Dropkin, executive director of Parks & Trails New York, a group that works to promote parks and trails throughout the state. “For an organization that has been advocating for multiuse trails for 25 years, this is beyond anything we ever imagined! This puts New York on the map as the trail state.”

Two Ways to Canada

The Hudson River Valley Greenway in New York City will form the southern tip of the EST once it’s complete. Traversing Manhattan from Battery Park to a bit north of the George Washington Bridge, often right at the water’s edge, this über-urban trail through the country’s most populated city is touted as one of the most heavily used bike paths in the United States. It offers views of the Statue of Liberty and New Jersey skyline and, looking inward, all the architecture the Big Apple is famous for. The display of buildings ranges from ultraluxe condos and skyscrapers galore to One World Trade Center, built to replace the fallen Twin Towers. At a symbolic 1,776 feet, the building is now the Western Hemisphere’s tallest.

This intensive urbanity stands in stark contrast to the farmlands, forests, smaller towns and bucolic landscapes found along most of the rest of the EST’s eventual route across the state. North of Manhattan, the trail will join the larger Hudson River Valley Greenway, itself a pastiche of dozens of smaller trails and historic sites. One award-winning section is a Rails-to-Trails Conservancy (RTC) 2016 Hall of Fame inductee, the Hudson Valley Trail Network. (Many trails in this area work the mighty Hudson into their name somewhere.) This section includes the celebrated Walkway Over the Hudson, a grand rail-trail built atop the 120-year-old Poughkeepsie-Highland Railroad Bridge. The whole of this north-south route cries out for the attention (and money) the EST will bring: While each completed segment offers a great experience, there’s no continuous pathway along the Hudson River Valley Greenway, resulting in a route that’s less than half complete.

In contrast to the Manhattan-Canada route, the Albany-Buffalo route is already more than 80 percent contiguous along an on-trail route. It follows the 360-mile-long Erie Canalway Trail, alternating between the modern barge way along the Mohawk River and the nearly 200-year-old original path of the Erie Canal—the first all-water link between the Atlantic seaboard and the Great Lakes. It’s hard to fathom the importance that such canals, simultaneously low-tech and ingenious, once played in U.S. history. These manufactured riverbeds provided mile after mile of smooth, linear waterway for mule-pulled barges that slashed the cost of long-distance transportation. Today, where the Erie Canalway follows the original canal, the route is the towpath that mules once clopped along.

William Sweitzer, director of marketing for the New York State Canal Corporation, the entity responsible for maintaining the Erie Canal, says the canal was one of the original keys to the country’s expansion. “Some called it the eighth wonder of the world; it opened up the West,” he says. In addition to cargo, the canal carried people, delivering untold numbers out of New York into the lands beyond—to the point where modern genealogists consider canal passenger lists an important resource for tracking the dispersion of 19th-century immigrants.

Into New York State

Today, in a welcome twist, the Erie Canal is bringing people into the state. “There’s been a boom in tourism, recreation and travel because of the canal and trail,” Sweitzer says. And the effects are being felt by businesses along the route; Sweitzer notes that he’s seen many shops reconsider what the canal-facing back end of their stores should look like, in places even reorienting their storefronts to provide a more beckoning welcome to trail users.

From wooden locks and sunken barges—still occasionally visible—to the Chittenango Landing Canal Boat Museum, the Canalway is packed with history, as Christine Hall O’Neil well knows. She’s the executive director of Chittenango Landing, the only recovered and recreated historic dry dock complex on the original Erie Canal.

Built around 1855, the site had everything a barge team—both the two- and four-footed members—might need. With carpentry and blacksmith shops, a sawmill, store and mule stable, “It was your Walmart and Home Depot right there,” says O’Neil.

The Erie Canalway terminates in Buffalo on the banks of Lake Erie, just across the Niagara River from Canada. In the future, biking adventures won’t have to stop there, though; Tom Sexton, director of RTC’s Northeast Region, points out that a completed EST will form the upper arc of an unfinished 1,400-mile circuit that will span four states and the nation’s capital, linking Buffalo, Syracuse, Albany, New York City, Trenton, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C. and Pittsburgh. “I should think about giving it a name soon because it’s 60 percent complete!” he jokes, noting that, “You can travel 335 miles today from Georgetown in D.C. to Pittsburgh [along the C&O Canal Towpath and Great Allegheny Passage] without ever leaving a trail.”

Adventures don’t even have to be limited to the U.S. It’s easy enough with a passport to cross from Buffalo into Canada across the Peace Bridge and from there to The Great Trail (formerly called the Trans-Canada Trail), a sprawling trail system traversing the Great White North.

The Plan

The Empire State Trail plan calls for 350 miles of gap-filling trails to be completed through 2020. The ambitious pace is made possible largely because the state already owns most of the land needed for the project, particularly along the Erie Canalway. The nitty-gritty of the route is still in flux, though, and not all sections will be so easily completed. One large segment along the Hudson River Valley Greenway, for example, crosses private property, though the state and landowner have begun negotiations. All told, the trail will cross through 27 counties.

Once complete, Dropkin says the EST will be about 70 percent on trail; along the more traversed Buffalo-Albany and Albany-Manhattan sections, that figure climbs to around 80 percent. In the more remote Albany-Canada route, “There will be more on-road connections,” she says. “If they’re safe and well marked, people will feel comfortable, but it has to be a fluid, seamless experience; that’s the goal.” She emphasizes that the EST won’t run roughshod over the trails already in place: “The existing trails won’t lose their own identity,” she says. “The Empire State Trail will be an enhanced identity.”

“The existing trails won’t lose their own identity. The Empire State Trail will be an enhanced identity.”

– Robin Dropkin, Executive Director, Parks & Trails New York

The Impact

More than just bridging gaps between cities, a completed Empire State Trail will bring the pathway to millions of residents who do not now have access to it. Take the city of Syracuse: While it is situated in the middle of the Erie Canalway’s historic route, there is no on-trail route through the city, creating a14-mile gap, among the longest on the Canalway. Choosing a route through the city presents one of the greater logistical challenges facing the EST, but one that will undoubtedly make an outsized impact.

Likewise in New York City, the Bronx currently has no paths that might be incorporated into the Empire State Trail. “It’s been a decade-long effort to create a link between the greenway in Manhattan and the greenway in Westchester County,” says Cliff Stanton, a coordinator with KRVC, a community organization that promotes cultural and economic development in the Bronx. “Ideally it would be an all-waterfront trail, like Manhattan’s. We’re looking for a practical solution with [the Metropolitan Transportation Authority] to create it.”

The land in question is owned by the MTA and sees active railway use. “In some parts of the line there’s enough room [for a rail-with-trail], but it’s quite a challenge in other parts,” Stanton says; developing a trail link there might require a more expensive build-out on the water to create a boardwalk. An alternative route being considered would move the path as much as a half-mile inland, but “it might as well be Mars,” says Stanton. “It doesn’t address our community’s desire to have waterfront access.” As it stands now, the only public access that 1.4 million Bronx residents have to the Hudson River is a 600-foot sliver of land accessible via a pedestrian bridge over the active railroad tracks.

In addition to connecting communities and providing recreational opportunities, there are concrete financial benefits to a state-spanning trail system. According to economic impact studies released by the governor’s office, users of the north-south Hudson River Valley Greenway already generate more than $21 million in annual economic impact among local businesses. The 1.5 million users of the east-west Erie Canalway Trail dwarf that, bringing in an estimated $253 million each year.

“Will [a completed] Empire State Trail help our museum?” muses Chittenango Landing’s O’Neil. “Absolutely!” she says, noting that her museum already draws a third of its traffic from the towpath trail. “It could be day-trippers just doing a section of the trail,” she says, adding that “through-riders doing the length” would benefit from a master trail tying the state together.

Proponents of the trail know that it’s about more than just dollars (welcome though they may be). Dropkin notes that while the canal indisputably opened up westward expansion, it “carried more than just goods and people. It was the birthplace of so many social movements—women’s suffrage, abolition—that it was called the burned-over district. So many social ideas caught fire there.”

Are we seeing another social movement today—one that values human-powered movement? “You could definitely apply the metaphor to biking,” Dropkin says.

Traveling through hundreds of communities in 27 counties, the 750-mile Empire State Trail will link three corners of the fourth-most-populous state in the nation.

Scheduled for completion in 2020, Gov. Cuomo’s plan calls for $200 million to be spent bridging gaps of approximately 350 miles in two major trails: the east-west Erie Canalway Trail and the north-south Hudson River Valley Greenway.

The plan will be completed in three phases: Phase One will plug 72 miles of gaps; Phase Two will eliminate 82 miles; and Phase Three will complete nearly 200 miles.

In total, about 70 percent of the EST will be on dedicated trails. The final 130 miles north past Lake Champlain to the Canadian border will probably be along State Bike Route 9, a signed, on-road route.

Trail surface will be as varied as the scenery and will encompass crushed stone, stone dust, brick pavers, asphalt and boardwalks.

Construction of the EST is projected to create an estimated 9.6 jobs for every $1 million invested. Likewise, every dollar invested will yield an estimated $3 in direct medical benefits for surrounding communities.

This article was originally published in the Spring/Summer 2017 issue of Rails to Trails magazine. It has been posted here in an edited format.

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.